Finding your way around the Roman Empire: Imperium Rōmānum

Saying where you live

Ubi: where?

Ubi habitās? Where do you live?

In Britanniā habitō. I live in Britannia.

The Romans called their world the orbis terrārum, ‘the circle of lands’ and you can see from the map below that they were concerned primarily with those territories which surrounded them on the Mediterranean (mare internum).

The first prōvincia Rōmāna (Roman province) outside Italy was Sicily after the Roman victory against the Carthaginians in the first Punic War. Romans occupied lands for different reasons: they wished to take the produce and natural resources, they could impose taxes, and acquire considerable manpower in terms of slaves or auxiliary soldiers. They sometimes felt threatened by neighbouring nations and created ‘buffer states’ (not unlike the old Soviet bloc), countries which surrounded them and would stand between them and potential invasion from more distant nations. Bithynia was bequeathed to the Romans, and Egypt fell to Rome after defeat in war.

By conquering another territory generals and emperors could gain political kudos; Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul afforded him considerable wealth and influence. Although Caesar sent expeditionary forces to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE, it was not until 43 CE that the actual occupation of Britannia took place – and that was on the part of Emperor Claudius whose own political position was insecure: by occupying Britain, he would win the support of the Roman people. Gnaeus Agricola, who was the commander of the occupying forces in Britain from 78-84 CE, had pushed into Caledonia (Scotland) and was also considering the occupation of Ireland (Hibernia) but he was recalled to Rome by the Emperor Domitian for fear that he was acquiring too much authority.

The Romans were very aware of other lands well beyond their own sphere of command. Objects excavated in the ruins of Pompeii were imported from regions, for example India and the Baltic, which were never under Roman authority.

What emerged was an empire of 60,000,000 people who, provided they did not challenge the dominance of Rome, lived comparatively uneventful lives. Some Roman provinces, however, were more challenging to manage than others, notably Judaea where rebellion against Roman rule led in 70 CE to the siege of Jerusalem, widespread massacre, and major destruction of the city. While it is true that Rome was often at war with somebody, and the military could be extremely brutal, such conflicts were localised. To focus exclusively on Rome’s military campaigns gives a highly skewed impression that Rome was a warmongering state when most of the inhabitants of its empire benefitted from common standards, roads, trade, water management systems, employment and, to a large extent, non-interference in local affairs.

Ablative singular of first declension nouns

A reminder: The word ‘case’ describes what function the noun is performing in the sentence, for example the subject or the object. ‘Declension’ describes the group to which a noun belongs depending on the endings the noun has. You can see from the map that almost all the territories in the empire end in -a: Britannia, Hispania, Germania, Africa. They are all first declension nouns. When used with the preposition in (a preposition is a word which describes where something or someone is) these nouns change to the ablative case:

Nominative: Britannia

Ablative: in Britanniā habitō

Nominative: Ītalia

Ablative: in Ītaliā habitō

At first sight there seems to be no change: both end in -a. In written Classical Latin there is no obvious difference because the macron was not used, but the macron (ā) shows that they were pronounced differently, the ablative ending being a long /ā/. Remember that, if you are writing in Latin, you do not need to use the macron and so, from the point of view of this case ending, there is - on paper - no difference.

[1] Practise saying where you live using these places:

Ubi habitās? > In Macedoniā habitō.

Belgica; Britannia; Gallia; Germānia; Hibernia; Hispānia; Ītalia

[2] You can now also say where you were born:

In Macedoniā nātus (m) / nāta (f) sum. I was born in Macedonia.

Note [i] the change: nātus, if a male is speaking, and nāta if a female is speaking, and [ii] that, in this construction, although you are using the verb ‘sum’, the entire phrase translates as I was born in …

Similarly, if you want to say where somebody else was born, change sum to est:

Amīcus meus in Caledoniā nātus est. My friend was born in Scotland.

Iūlia in Ītaliā nāta est. Julia was born in Italy.

Practise saying where you were born using these places:

Arabia; Asia; Calēdonia; Dācia; Libya; Maurētānia; Thrācia

Note! You might be tempted to say which town or city you live in or were born in. Avoid the temptation because in + ablative is not used with the names of towns and cities; another construction known as the locative is required to be able to express that and so, for the moment, stick to countries!

Saying where you are

Ubi es? Where are you?

In viā sum. I’m in the street.

Esne in viā? Minimē, in culīnā sum. Are you in the street? No, I'm in the kitchen.

Ubi est liber meus? In mēnsā est. Where's my book? It's on the table.

Estne fīlius meus in scholā? Minimē, in caupōnā est. Is my son in school? No, he's in the pub.

‘in’ can mean ‘in’ or ‘on’; here are some other places where you might be:

basilica [nominative] law court > in basilicā sum: I’m in the law court.

culīna (kitchen) > In culīnā sum: I’m in the kitchen.

īnsula (island) > In īnsulā sum: I’m on an island.

Now do the same with these nouns:

curia (senate house) > In …. sum.

silva (forest) > In ….

taberna (shop) > …

vīlla (country estate) > …

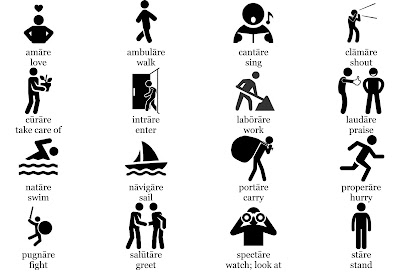

And then try using the same expressions with the images posted.