A quick reminder: all of my posts since 02.05.24 have been

based on this video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nY1FVZ9fUl8

Almost everything that Vincent said on that video has been

used for review.

Note the two words in block capitals in the text:

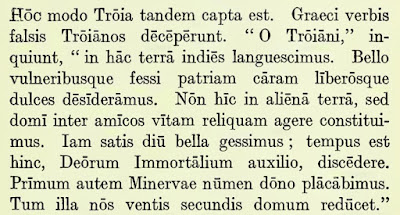

Hōc modō Troia tandem capta est. Graecī verbīs

falsīs Troiānōs dēcēpērunt. "Ō Troiānī," inquiunt, "in hāc terrā

in diēs languēscimus. Bellō vulneribusque fessī patriam cāram līberōsque dulcēs

dēsīderāmus. Nōn HĪC in aliēnā terrā, sed domī inter amīcōs

vītam reliquam agere cōnstituimus. Iam satis diū bella gessimus; tempus

est HINC, Deōrum Immortālium auxiliō, discēdere. Prīmum autem

Minervae nūmen* dōnō plācābimus. Tum illa nōs ventīs secundīs

domum redūcet."

[In this way Troy was finally taken. The

Greeks deceived the Trojans with false words. "O Trojans," they said,

"we have been languishing in this land day after day.

Tired of war and wounds, we long for (our) dear country and sweet children.

Not HERE in a foreign land, but at home among friends, we have

decided to spend the rest of our lives. We have fought wars long enough; it is

time to depart FROM HERE with the help of the immortal gods.

But we will first appease the divine will of Minerva with a gift. Then she will

bring us back home with favourable winds."]

*nūmen, nūminis [3/n] its basic meaning is a ‘nod of the

head’ but very often when the gods are involved it refers to divine

will.

Notes:

[1] Google translate alert!

Beware the Greeks bearing gifts.

Beware Google giving translations.

What it is: Tum illa nōs ventīs secundīs domum

redūcet. │ Then she will bring us back home with favourable winds.

What Google Translate thinks it is: Then

she will bring us home in twenty seconds.

[2] in hāc terrā in diēs languēscimus │

we have been languishing in this land

day after day

French and German speakers will get this straight away:

I’ve been living here /

I’ve lived here for three years (and I still am).

Fr: J’habite ici depuis trois ans; Gmn: Ich wohne seit drei

Jahren hier; both French and German (and Russian) literally express this by

using a present tense i.e. I am living here since three years.

Russian often uses uzhe (already) with a present tense to

convey that.

Latin does the same; it uses a present tense often

with iam (already) or other expression of time to express an

action that started in the past and is still happening:

in hāc terrā in diēs languēscimus │

we have been languishing in this land

day after day [literally: we are languishing in the land day after day (and we

still are)]

There is no separate Latin verb form that expresses the

English “have been doing something”.

[3] In the video, Vincent said:

Et vidētur frāter meus illīc │ And my

brother is seen / can be seen over there.

hīc and illīc

[i] vocabulary lists sometimes miss the spelling difference:

hīc – with long /ī/ - means ‘here’

[ii] illīc: (over) there

There is a little ‘bunch’ of these which you need to be able

to recognise; it’s best to visualise them and so they are posted with images

because they have “fussy” differences which aren’t always easy to remember!

Here they are listed with examples, but the only way I could

recall them was to visualise them; check the image.

[1]

hīc: here

hūc: to here (in older English we used to say hither)

hinc: from here

[2]

illīc: (over) there

illūc: to there (in older English we used to say thither)

illinc: from there

From the texts:

Nōn hīc in aliēnā terrā, │ Not here in

a foreign land …

tempus est hinc … discēdere. │ It is time

to depart from here …

From the video:

Et vidētur frāter meus illīc │ And my

brother is seen / can be seen over there.

Further examples from the authors:

[1]

Hīc semper in lūctū manēbō (Gesta Rōmānōrum) │ I

shall always remain here in mourning.

Vāde, vocā virum tuum, et venī hūc.

(Vulgate)│Go, call your husband and come (to) here.

Abī hinc(Livy) │ Go away from here …

[2]

Illīc sum atque hīc sum.

(Plautus) │I’m here and there.

Saepe tamen illūc ībat (Gesta Rōmānōrum) │

However, he would still often go (to) there.

num … mulier illinc vēnit? (Plautus)

│Hasn’t the woman come from there?