“Take a foreign

language, write it in an unfamiliar script, abbreviating every third word, and

you have the compound puzzle that is the medieval Latin manuscript.” (Adriano

Cappelli)

Medieval

manuscripts were heavily abbreviated to save parchment and ink. At first sight,

they seem to be a real uphill climb because it does involve a lot of study,

individual handwriting – both then and now – differs, and there are thousands

of abbreviated forms. Despite that, there is, I feel, a fascination in

deciphering the handwritten work of an author or scribe from the Middle Ages;

it’s the closest you’ll get to that person actually being with you.

Commenting on

Capelli’s work, Heiman and Kay, the translators, state: “in nine cases out of

ten he (the reader) could ascertain the meaning by applying a few simple rules”

i.e. there are common features in the manuscripts.

Points to note:

[i] The rules

governing abbreviations were flexible; scribes did not adhere to them exactly.

However, there are general patterns and context usually allows the reader to

identify which letters are to be supplied for the abbreviation.

[ii] The patterns

discussed here refer only to the text we’re dealing with. While these are

common patterns, it does not follow that what they represent in this text

consistently applies to others, but they are a good start to “cracking the

codes”.

[iii] If you’re

reading a manuscript, try to find as high a resolution as possible

because you very often need to magnify the text to get up close and personal

with the scribe, examine his handwriting and look for patterns in

both the way he forms his letters and the style / types of abbreviations he

uses.

[iv] A single

document can be difficult to decipher since you have nothing to compare it

with. The Tacuinum Sanitatis is a large work, and so, when uncertain,

I was able to cross-reference to establish the pattern of his handwriting style

and the way in which he uses abbreviations elsewhere.

[v] In the case of

this text, I was lucky to find a complete transcription from a reliable

source but no transcription using the original symbols and abbreviations.

Nevertheless, by using the transcription you can “reverse engineer” it by

comparing the full Latin words with the original manuscript to identify exactly

what’s going on.

Terminology

Let’s first

consider some English abbreviations – because the scribes are doing something

similar:

[1] etc. = [i] et ¦ [ii] c(etera); [ii] is

abbreviated by truncation, only the first letter is written, the

abbreviation usually indicated by a full stop [.]

e.g. │ e(xempli)

g(ratia): for example

Fri(day),

Oct(ober)

Nowadays, truncation

is used all the time in text messages:

brb │ be right

back i.e. an assumption is made that the reader is familiar with the

abbreviation or can work it out from context

[2] hr │ hour;

abbreviation by contraction, the middle letters omitted

asst │

ass[i]st[ant]: contraction and truncation

English contracts

all the time by combining two words – sometimes more than two - into one, not

always standard but done to reflect speech:

I’ve │ I have;

he’s │ he is; I’d’ve │ I would have

[3] siglum:

letters or symbols used to represent words

From the Romans: C

│ 100

One symbol we use

every day: @ = at

Mathematical

symbols represent words; one of them (+) appears in this text to represent

‘and’

It doesn’t appear

in this text but we still use one from the Middle Ages: & ‘ampersand’ │ and

[4] superscript:

letters which mark the ending of a word e.g. 1st, 2nd

All I’ll do here

is pick out the common features of this particular text.

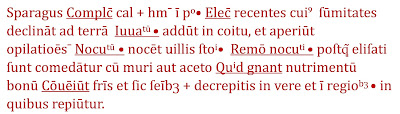

Image Set #1

As in English

there can be:

[i] abbreviation

by truncation; only the first part of the word is written out:

ca │ calida

[ii] abbreviation

by contraction; one or more of the middle letters are missing:

gnant │ generant

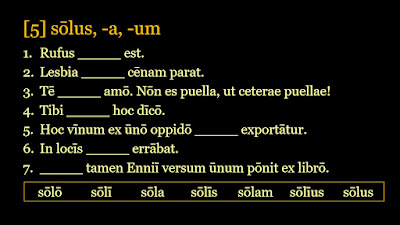

Image Set #2

A line, horizontal

(e.g. ū) or wavy (resembling the Spanish tilde e.g. ũ) written over a letter

indicates that some letters have been omitted. Usually these letters are m

or n, but this is not always the case.

combining

overline [ ¯ ]

aperiūt │

aperiunt

comedātur

│ comedantur

cōuēiūt

│ conueniunt

cū │ cum

declināt ad

terrā │ declinant ad terram

nutrimentū

bonū │ nutrimentum bonum

nocēt │

nocent

The final image of

Set #2 (opilationes) shows that the line, despite it indicating the absence of

/n/, is written above the final letters

Some writers

describe the mark as a macron, but, in Latin, we use that term now to

refer to the indication of long vowels e.g. puellā, fēmina, vīnum,

ōra, ūrit. However, in a Mediaeval manuscript, a line is not

indicating a vowel length.

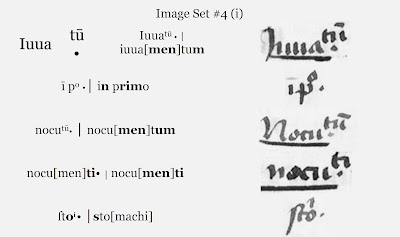

Image Set #3

The line does not always indicate the omission of /m/ or /n/

but simply acts as an indicator of abbreviation:

frīs │ frigidis

[a good example where you need to look at his handwriting style, in this case

the formation of /s/ at the end of a word]

remō │remotio

The first title – complectio

– is interesting in that, in other parts of the manuscript (which we are not

looking at here), he abbreviates it in different ways: compl’ / compł / compło

/ complō

In this text he

uses c̄ [complc̄] and also in the

second title: elc̄

[electio]; at first sight, it may look like an /e/ but, examining his

handwriting in other parts of the manuscript, he forms /c/ in the same way;

you can see that formation (looking more like /r/ than /c/) in, for example: ca(lidus)

/ coitu / cū (cum)

Compare the letter

formations in Image Set #3 (ii)

Horizontal lines through letters: q,

p, b, l, h, t with a horizontal or diagonal

line through them, indicate that some letters were omitted which needed to be

supplied by the reader.

The most common letters with a horizontal line were p and q,

and they are both in the manuscript:

[1] reꝑiūtur

│ reperiuntur: it’s difficult to see because it is partially

masked by a red line, but there is a stroke through the letter p: ꝑ

When this happens it can assume different meanings; in this

case ꝑ │ per

(but in other manuscripts it can be, for example, par or por or pre)

[2] poſt¦ꝗ̃ │post¦quam

i.e. the sign represents an entire word

The letter which looks like a 9 indicates /us/ (but can also

indicate -os, -is or just -s); it has a distinctive position always written

above the line and at the end of a word. It can appear in other positions with

a different meaning, but it is the meaning here in the text that concerns us.

cuiꝰ │

cuius