In the first post on cases, it was explained that Latin nouns have endings depending on what function they perform in a sentence. You already saw a small example of this when looking at the vocative case e.g.

Nominative: Mārcus

Vocative: Mārce

Nominative: Iūlius

Vocative: Iūlī

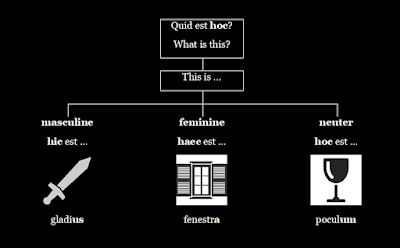

However, the case endings are not the same for all nouns. Latin nouns are placed into one of five groups depending on the endings which they have. These groups are called declensions. Here, we are looking at two declensions:

[1] nouns ending in -a belong to the first declension

[2] nouns ending in [i] –us and [ii] –um belong to the second declension

[1] Most nouns in the first declension are feminine in gender although, as you have already seen, a few which refer to occupations that were associated with males are masculine. Nevertheless, they all take the same endings.

- ancilla: maidservant

- Hispānia: Spain

- magistra: teacher (f)

- mēnsa: table

- Rōma: Rome

- taberna: shop

A few examples of masculine nouns in the first declension:

- agricola: farmer

- aurīga: charioteer

- poēta: poet

[2] [i] Nouns ending in -us in the second declension are almost all masculine, although, again, there are a few which are feminine but they take the same endings.

- amīcus: friend

- calceus: shoe

- fīlius: son

- lectus: bed; couch

- oculus: eye

- sagittārius: archer

While there are quite a few second declension nouns in -us which are feminine, many of them are very rare. Below are some more common ones:

- Aegyptus: Egypt

- fāgus: beech tree

- humus: ground

- pīnus: pine tree

- pōmus: fruit; fruit tree

A small group of nouns ending in -er and -ir also belong to the second declension; they are all masculine, for example:

- ager: field

- liber: book

- vir: man

[ii] Nouns ending in -um in the second declension are neuter.

- Eborācum: York

- librārium: bookcase; library

- Londinium: London

- tēctum: roof

- tēlum: javelin

- vīnum: wine

Take a look at the words below; to which declension (first or second) do they belong? It’s a straightforward task because all you have to do is look at the ending. Don’t be concerned by the meanings of some of these words; the new words will come in the next post.

- argentārius

- armārium

- ātrium

- Britannia

- cubiculum

- culīna

- discipulus

- fenestra

- fluvius

- galea

- gladius

- hortus

- magister

- mēnsa

- nūntius

- papȳrus

- peristȳlium

- plaustrum

- pōculum

- puer

- sella

- signifer

- stilus

- tabula

- templum

- trīclīnium

- via

In the next post, you will begin to see how crucial it is to know to which declension a noun belongs.

The image below summarises the endings of the first and second declension.