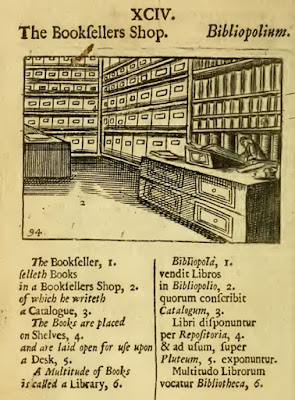

Comenius: Orbis pictus (First edition: 1658; Engl. transl.

by Hoole: 1659)

It’s interesting to note three points about this book:

[1] It was the first widely used illustrated textbook for

children

[2] It became a best-seller in Europe for a hundred years.

[3] It is based on topics, not on grammar i.e. the language

was designed to be spoken, for the kids to talk about the world around them

bibliopōla │ the bookseller

vēndit librōs │ sells books

in bibliopolīō │ in a bookseller’s shop

quōrum cōnscrībit │ of which he writes

catalogum │ a catalogue

librī dispōnuntur │ the books are placed

per repositōria │ on shelves

& [et] ad ūsum, super │ and are laid open for

use upon

pluteum expōnuntur │ a desk

multitūdō librōrum │ a multitude of books

vocātur bibliothēca │ is called a library

vocabulary and notes

bibliopola, -ae [1/m]: bookseller

bibliopōlīum, -ī [2/n]: bookshop; New Latin, but not that

“new” since Comenius is using it

bibliothēca, -ae [1/f]: library; a room for books

pluteus, -ī [2/m]: bookshelf; Hoole, the translator,

describes it as a ‘desk’; although we associate the word with a complete piece

of furniture, “desk” can also refer to a lectern i.e. the sloped surface on

which the reader places the book, one which, in this case, seems to be bigger

than the reader himself!

repositōrium, -ī [2/n]: it has a vague dictionary

description of “something on / in which something else is placed” (Lewis and

Short) but it can refer to a tray or a cabinet; the translator writes “shelves”

but there also appear to be labelled storage boxes to the left of the image

librārius, -a, -um: pertaining to books

taberna, -ae [1/f] librāria: bookshop

librārium, -ī [2/n]: a place to keep books e.g. a

bookcase or bookshelf

Note [1]

-ārium

Note: -ārium; this suffix is used to refer to the purpose of

the noun, for example it often indicates where something is kept

armārium, -ī [2/n] (literally: a place for storing weapons);

cupboard

alveārium, -ī [2/n]: beehive

aquārium, -ī [2/m]: a watering place for cattle

sōlārium, -ī [2/n]: a terrace exposed to the sun; sundial

Technically, -ārium should be attached to a noun

e.g. liber + -ārium > librārium i.e. a place for books

However, it can be found with adjectives; the logic behind

these three in the Roman bathhouses is obvious:

[i] from caldus, -a, -um: hot > caldārium, -ī [2/n]: warm

bath; the place where hot water is kept

[ii] from frīgidus, -a, -um: cold > frīgidārium, -ī

[2/n]: the cold room

[iii] from tepidus, -a, -um: warm > tepidārium, -ī [2/n]:

the warm room

Note [2]: three examples of the passive:

[i] dispōnō, -ēre, disposuī [3]: distribute; arrange

Passive:

librī dispōnuntur │ the books are placed /

arranged

per repositōria │ on / along shelves

[ii] expōnō, -ere, exposuī [3]: display; set out

librī … super │ and are laid open for use

upon

pluteum expōnuntur │ a desk

[iii] vocō, -āre, -āvī [1]: call

Passive:

multitūdō librōrum │ a multitude of books

vocātur bibliothēca │ is called a

library

i.e. X is called Y