One of the quotations in the previous post is from Cicero’s speeches against Verres, the latter on trial for the mismanagement of Sicily. Cicero was the prosecutor. If you’re already reading some of the literature, there’s an important feature in the complete quotation.

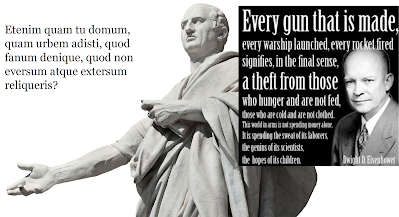

Etenim [1] quam tu domum, [2] quam urbem adisti, [3] quod fanum denique, quod non eversum atque extersum reliqueris?

In truth, [1] what house, [2] what city, [3] what temple even have you ever approached without leaving it emptied and ruined?

This is called a tricolon, a series of three parallel words or phrases or sentence clauses which are identical, or almost identical, in structure. Note how Cicero leaves the most dramatic one until last: not only does Verres ruin [1] houses and [2] cities, but [3] even disgraces the gods. The translator well conveys that with “what temple even”.

Cicero makes extensive use of the tricolon, and it is still

used today:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired (President Eisenhower)

And when the night grows dark, when injustice weighs heavy on our hearts, when our best-laid plans seem beyond our reach (President Obama)

You are talking to a man who has laughed in the face of death, sneered at doom, and chuckled at catastrophe. (The Wizard of Oz)

And from Dorothy Parker:

I require three things in a man. He must be handsome,

ruthless, and stupid.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/nov/26/barack-obama-usa1

I’ve mentioned in earlier posts that quotations are only posted if they’re relevant. In the next post on the perfect tense, the most famous tricolon of them all is relevant.

vēnī, vīdī, vīcī