Quid edis / bibis in prandiō / cēnā? What do you eat / drink at lunch / dinner?

- prandium: lunch

- cēna: dinner, the

principal meal of the day

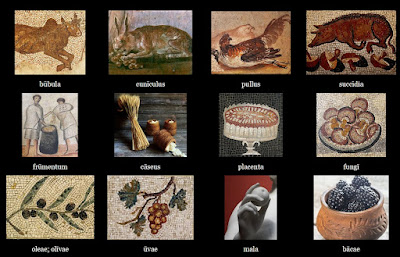

All the words in the images

are 1st or 2nd declension nouns. However, the general word for ‘meat’ is carō;

it is a 3rd declension noun: Carnem edō. And so, just become

familiar with the word rather than analyse why it ends the way it does.

The same applies to the word

for 'fish' piscis: it, too, is 3rd declension; Piscēs edimus (we

eat fish; in Latin the plural of piscis is used).

Below are some notes on

vocabulary not discussed in the previous post.

acētāria (neut. pl)

This refers to something

which is prepared with oil and vinegar e.g. vegetables and, therefore, salad

būbula

vacca: cow; taurus: bull,

but būbula (beef)

frūmentum

grain, part of the staple

diet of the Romans; the lack of it would have been a source of real concern and

is referred to in the literature.

garum

You might use ketchup

nowadays, but the Romans used garum, a fermented fish sauce, to

enhance the flavour of their dishes. High quality garum could fetch very high

prices. One of the wealthiest citizens in Pompeii was a garum merchant.

placenta

This word did not have the

biological associations that it does now. It refers to a type of cake

consisting of several layers of dough interspersed with cheese, honey and bay

leaves. It was then baked and covered in honey.

posca

Posca was a low-quality

watered-down wine mixed with herbs and spices, popular among the military but

shunned by the upper classes.

mulsum

Considered to be the oldest

alcoholic drink in the world, mulsum is the sweet Roman

mixture of wine and honey. Wild grapes were not as sweet as they are now and so

honey was added. Mulsum is also known as ‘mead’.

cervisia: beer (alternative

spellings cervēs(i)a; cerevisia); the word is of Celtic origin. And so, if

you’re on a trip to Ibiza, and you proudly state to the waiter in Spanish “Una

cerveza, por favor”, you know where the word came from!

The Vindolanda tablets

At the time they were discovered, the Vindolanda tablets were the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain providing a rich source of information about life on the northern frontier of Roman Britain. The documents record official military matters as well as personal messages to and from members of the garrison of Vindolanda, their families, and their slaves (adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vindolanda_tablets )

One, however, is of

particular interest which was sent by Masclus, a Roman cavalry officer, to

Flavius Cerialis, the prefect (military official) who lived at Vindolanda. The

date is estimated at 97-105 CE.

cervesam commilitones non

habunt quam rogo

iubeas mitti

My fellow-soldiers have

no beer. Please order some to be sent.

You can see the original

document below; no marks, though, for handwriting or the peculiar use of habunt (2nd

conjugation is habent; Masclus wasn't spot on in Latin grammar!)

Look at the post on the

formation of 3rd conjugation verbs, and then look at these verbs:

- bibere (to drink)

- coquere (to cook)

- edere (to eat)

- emere (to buy)

- quaerere (to look for)

- sūmere (to take)

- vēndere (to sell)

Have a try at completing the

Latin sentences below using these verbs. The English translations are given to

help you. Remember to check the verb endings!

- Quid in culīnā ____?

- Quid in tabernā ____?

- ____nē olīvās?

- Ūvās nōn ____.

- Rōmānī frūmentum ____.

- Lupus in silvā cibum

____.

- Sextus ientāculum in

hortō____.

- Cervisiam ____ nōn amō.

- What are you (sg)

cooking in the kitchen?

- What are you (pl)

buying in the shop?

- Do you (sg) sell

olives?

- We don’t sell grapes.

- The Romans eat grain.

- The wolf is looking for

food in the forest.

- Sextus takes breakfast

in the garden.

- I don’t like to drink

beer.