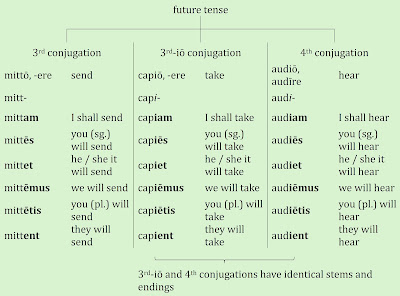

This little text shows you both future tenses working

together. The verbs in bold are 3rd and 4th conjugation, the verbs in italics

1st conjugation.

Again, note the characteristic -bō / -bi- / -bu- of the 1st

(and 2nd) conjugation and, this time, the characteristic –(i)am / -(i)e/ē- of

the 3rd and 4th.

PŪBLIUS ET SERVIUS

[Chesnutt: the Road to Latin (1933)]

Pūblius et Servius

in hortō lūdunt. Prope puerōs parvōs Tullia cum amīcā Camillā sedet. Fēminae

puerōs spectant et audiunt.

“Nōn

semper,” inquit Pūblius, “parvī erimus. Tum nōs quoque cum Lūciō et Aulō

Rōmam ambulābimus.” Mox discipulī erimus et cotīdie ad lūdum properābimus,”

respondet Servius. “Quid in ludō agēs?” rogat Pūblius. “In lūdō

fābulās legam,” respondet Servius. “Tūne, Servī, semper

fābulās legēs?” Interdum lūdī magister fābulās leget.

Fābulās dē deis et deābus leget,” respondet Servius. “Nōs in lūdō

multās fābulās legēmus!” clāmat Pūblius.

“Quālēs fābulās,

meī fīliī, legētis?” rogat Tullia. “Fābulās dē bellīs et dē

aurigīs legēmus,” respondent Pūblius et Servius.

“Meī

fīliī parvī, Camilla,” inquit Tullia, “Libenter fābulās legent.

Fortasse domī fābulās nārrābunt.” “Parvī fīliī tuī sunt cārī,

Tullia. Fortasse ad vīllam meam mox venient. Nunc domum properābō.

Nōnne ad lectīcam, puerī, veniētis?” rogat Camilla. “Veniēmus sī

Tullia quoque veniet,” respondent puerī. “Cum fīliīs parvīs,”

inquit Tullia, “libenter veniam. Nōnne iterum, cāra Camilla, ad

vīllam veniēs?” “Mox veniam et fīliae meae

quoque venient,” respondent Camilla.

lectīca, -ae [1/f]: sedan; portable sofa / couch [see image]

quālis [masc. / fem.] quāle [neut.]: what kind of?

[1] Two future tense verbs are the focus of the text:

[i] legō, legere [3]: read

legam: I shall read

legēs: you (sg.) will read

leget: he / she / it will read

legēmus: we will read

legētis: you (pl.) will read

legent: they will read

[ii] veniō, venīre [4]: come

veniam: I shall come etc.

veniēs

veniet

veniēmus

veniētis

venient

[2] Note again the variation in tense usage between Latin

and English:

Veniēmus [future] ¦ sī Tullia quoque veniet [future]

We will come [future] ¦ if Tullia also comes [present]

[3] “Quid in ludō agēs?” rogat Pūblius.

agō, agere [3]: do

Publius asks a useful question: What will you do in

school? We will use that question later to do more practice of the future

tense.