Image #1: A great deal of detail is given with regard to numbers but if your aim is primarily reading then that is classified as a passive skill: our passive vocabulary is larger than our active vocabulary. We may recognise a word even though we might rarely, or possibly never use it in our own speech and writing. Therefore, the need is to identify the meaning of a number without necessarily becoming involved in declensions or being distracted by minor changes in spelling of related numbers.

trēs │ three

tredecim │ thirteen

duodētrīgintā │ twenty-eight [i.e. 2 from 30]

ūndētrīgintā │ twenty-nine [i.e. 1 from 30]

trīgintā │ thirty

trecentī │ three hundred

Focus on the “markers”, those parts of the word that

indicate [i] the teens [ii] multiples of ten and [iii] multiples of 100.

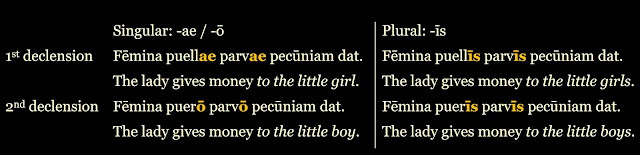

Image #2: Here are the five key pieces of information, the five

‘markers’ you need to “unlock” numbers:

-decim │ teens

-gīntī; -gintā │ multiples of ten

-centī; -gentī │ multiples of 100

duodē- │ two from the next number [i.e. number compounds ending in 8 e.g. 18, 28 etc.]

ūndē- │ one from the next number [i.e. number compounds ending in 9 e.g. 49, 79 etc.]

Apart from vīgintī (20), centum

(100) and mīlle (1000) all cardinal numbers in Latin beyond 10, are formed from

numbers 1 – 10.

Provided you know [a] those markers

and [b] the existence of ūn¦dē- and duo¦dē-, all other numbers

can be easily recognised despite variations in the spellings or when some

of those numbers decline.

When reading Latin don’t be

distracted by thinking about the spelling changes or why a number has a

particular ending but simply identify the number.

[1] teens: -decim

Base number + decim; the spellings of the base

numbers may change but the root is still clear

duo │ two > duo¦decim │ twelve

trēs │ three > tredecim │ thirteen

sedecim │ sixteen

Watch out for duodē- and ūndē- because they are used with

the next number to come:

duo¦dē¦vīgintī [ = 2 from 20] │ eighteen [i.e.

not 22]

ūn¦dē¦vīgintī [ = 1 from 20] │ nineteen [i.e. not

21]

[2] multiples of ten: -gīntī; -gintā

The number vīgintī (20;

Fr. vingt; It. venti; Sp. veinte; Port. vinte) itself cannot be deduced from

any other number. If you’re a coffee drinker, you may well have seen the

Italian word venti in coffee houses referring to a 20 ounce measure.

All the other multiples of ten are formed with a

recognisable base number + -gintā; again, spellings will change but the

base number is still identifiable, for example:

trīgintā │ thirty

quadrāgintā │ forty

duo¦dē¦quīnquāgintā [2 from 50] │ forty-eight

quīnquāgintā │ fifty

nōnāgintā │ ninety

ūn¦dē¦centum [1 from 100]│ ninety-nine

centum: like viginti, it has a unique form not from

any other number but, of course, evident in century and cents

[3] 100 and multiples of 100: -cent(ī); -gent(ī)

all the numbers in

the 100s are formed as multiples of cent(um) i.e. centī

or gentī; the multiples of 100 decline and the final -ī may change but

the markers -cent- and -gent- remain

The existence of

/g/ in both the multiples of ten and the multiples of 100 can cause a

misreading. Therefore, note carefully the vowel differences between:

[a] -gĪntī /

-gIntā: markers of multiples of ten; quadragIntā │ forty

[b] -cEntī / -gEntī : markers of multiples of 100; quadringEnti │ four

hundred

ducentī │

200

quadringentī │400

septingentī │700