The gerundive was

first referred to in the following two posts:

[1] https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/08/260924-level-2-ora-maritima-24-and-25-6.html

[2] https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/11/120225-level-2-reading-schoolmasters.html

[i] laudandus,

-a, -um: gerundive; it is adjectival i.e. it agrees with the noun

in gender, number and case

[ii] the literal

meaning is: to be Y-ed, for example:

mīles laudandus

│a soldier (who is) to be praised

epistula scrībenda│

a letter (which is) to be written

dēdit mihi epistulam

legendam tuam (Cicero) │he gave me your letter to read [ = (which

was) to be read]

deinde eum … redūcendum Faleriōs

puerīs trādidit (Livy) │ he then handed him to the boys to

be taken back to Falerii

Gravis iniūria

facta est et nōn ferenda. │ A grave and intolerable wrong has

been done, i.e. a wrong ¦ which is not to be tolerated

Gerundives exist

in English derivatives:

agenda:

things that are / need to be done (usually during a meeting)

memorandum

(pl. memoranda): a reminder, something that is to be remembered

addendum

(pl. addenda): something which is to be added, usually at the end

of a document

corrigendum

(pl. corrigenda): an error that is to be corrected in a book

after publication

2 English proper

nouns:

Amanda

(literally: she who is to be loved)

Miranda

(literaly: she is who to be wondered / marvelled at)

[iii] Because it

is referring to something that is to be done it can also refer to as a future

passive participle

[iv] It is formed

from the stem of the present tense with a distinctive -nd- ending + the

adjective endings -us, -a, -um; below are its forms with its basic meaning

laudō, laudā¦re

[1] > lauda- > lauda¦nd¦us, -a, -um │ which is to be

praised (future passive participle i.e. something that is to be done in the

future)

timeō, timē¦re [2]

> time- > timendus, -a, -um│ which is to be feared

dūcō, dūce¦re [3]

> dūc- > dūcendus, -a, -um│ which is to be led

3-iō and 4th

conjugation have -ie- before the ending is added

capiō, cape¦re

[3-iō] > capie¦nd¦us, -a, -um│ which is to be captured

audiō, audī¦re [4]

> audiendus, -a, -um│ which is to be heard

[v] The most

frequent use of the gerundive is with esse. In grammar this is known as

the passive periphrastic, a term that sound intimidating, but all it

means is that more than one word is required to express the idea. Unlike

English, the overwhelming majority of Latin verbs simply need a single word to

express the idea e.g. veniēbat (he was coming), laudāmur (we are

praised) whereas a periphrastic construction needs more than one.

The verb esse

can be in the present, imperfect or future tense:

Hoc faciendum est. │ This must be / has

to be / needs to be done.

Hoc faciendum erat. │ This had to be / needed

to be done.

Hoc faciendum erit. │ This will have to be done.

Depending on

context, the translations can be flexible depending on whether something ought

to be / should be done or needs to be / must be done:

Hic liber legendus

est. │ Literally: This book is to be / needs to be / should

be / worthy of being read =

this book is worth reading.

Carthāgō dēlenda

est. │ Carthage must / should be destroyed.

Mīles laudandus

erat. │ The soldier was to be praised = the soldier was praiseworthy.

[vi] If the action

that needs to be done includes who needs to do it i.e. the agent,

then the dative is used to express it. The gerundive conveys a sense of obligation

and it is given that grammatical term: the gerundive of obligation.

Carthāgō nōbīs dēlenda

est. │ Carthage is to be destroyed by us i.e. even though the

translation is ‘by us’ (which would suggest an ablative), it is the

dative that expresses the idea in this construction.

It would be

perfectly possible to rework the sentence from a passive to an active meaning:

Carthāgō nōbīs dēlenda

est. │ Carthage is to be destroyed by us > We must destroy Carthage.

English can convey

a similar idea:

Hic liber tibi

legendus est │literally: this book is to be read by you > this book is for you to read > you

need to read this book

[vii] In all the

examples above, there is a subject since the construction conveys [X: noun]

needs to be Y-ed

Hic liber legendus est. │ This book needs to

be read.

Carthāgō (nōbīs) dēlenda est. │ Carthage

must be destroyed (by us)

However, the

neuter singular of the gerundive + esse can express an impersonal idea

i.e. there is no noun subject to which something needs to be done.

Mihi currendum est │I need to

run; the gerundive here indicates the agent must perform that action.

Sometimes, no

agent is indicated i.e. there is simply a neuter gerundive with esse;

context will determine how that is best translated, for example:

Pugnandum est │

(I, you, we etc.) need to fight i.e. there is need for fighting; even though no

agent is indicated, it is usually best to include a subject.

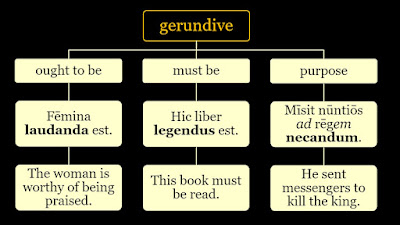

In the next post

we will look at a further use of the gerundive, namely to express purpose i.e.

the third column in the first image.