Sunday, April 7, 2024

29.02.24 Progress check

When we were learning to ride bicycles, most of us first fell off several times, then wobbled a lot and then, finally, began to cycle. Very few of us learned to swim when our fathers threw us on day one into a pool and said “swim!” Learning is a process: some knowledge comes easily to us and some requires review. We trip up, we forget but we don’t give up. We can look again at information, study it more thoroughly and have another go.

[A] Here are some questions based on what has been covered so far. You can check your own progress by applying some very simple criteria:

Ubi habitās?

[i] Do you understand the question even if you’re not sure how to answer? If yes, give yourself one point.

[ii] Can you answer it with a ‘yes’ / ‘no’ or a simple phrase i.e. can I respond to show understanding? If yes, give yourself 2 points.

Ubi habitās? Ītalia (in Ītaliā would be better, but at least you gave a reply). And be self-critical; perhaps you gave a full answer but with a minor grammatical error = 2 points

[iii] Can you give a full and grammatically correct answer? If yes, give yourself three points.

Ubi habitās?

In Ītaliā habitō.

So, can you understand and speak Latin? Here goes, and remember that you don’t have to tell the truth! If you don’t know how to say that you work in a graphic design department, then say you work in the Colosseum! Total marks: 60

1. Quid agis?

2. Quid nōmen tibi est?

3. Quot annōs nātus / nāta es?

4. Unde oriundus / oriunda es?

5. Ubi habitās?

6. Habitāsne in oppidō vel in urbe?

7. Quid est in oppidō tuō / in urbe tuā?

8. Ubi labōrās?

9. Habēsne fīlium?

10. Quid nomen eī est?

11. Estne tibi fīlia?

12. Quot annōs nāta est?

13. Suntne tibi frātrēs vel sorōres?

14. Quae sunt nōmina eōrum?

15. Habitāsne in domō vel in fundō?

16. Quid est in culīnā tuā?

17. Quid est in cubiculō tuō?

18. Habēsne ancillās?

19. Amāsne vīnum?

20. Natāsne in fluviō?

[B] And have a bit of fun with a Modern Language style role-play:

[i] You’re buying food.

Greet the shopkeeper and ask him how he is.

Bene, gratiās tibi agō. Et tū?

Answer his question and ask him if he has olives.

Ita, quot olīvas desiderās?

Say that you want ten.

Quid aliud?

Say that you want eight eggs and four oysters.

Ostreās nōn habeō.

Ask where they have oysters.

Ostreās in forō piscātoriō habent.

[ii] You’re meeting somebody for the first time. Think of five relevant questions in Latin that you could ask that person.

[C] How much about Roman life have you picked up from the posts? Here are some background questions.

1. Who in a Roman family is the pater familias?

2. Where would guests be taken in a Roman house?

3. What was the purpose of a ‘compluvium’ in a Roman house?

4. How did the Romans keep their houses [i] cool, and [ii] lit at night?

5. What could you buy in the ‘forum olitorium’?

6. What could you buy in a ‘thermopolium’?

7. What would you do at the ‘thermae’?

8. ‘Insula’ can mean ‘island’ but to what type of housing did it refer in a city?

9. Why would it be important for a city to have ‘moenia’?

10. Where would you have seen ‘venationes’?

11. What was the job of a ‘lanista’?

12. Romans did not have pens and pencils. What did they use to write with, and what did they write on?

13. What is the origin of the English word ‘pen’?

14. What was kept in a ‘capsa’?

15. How does our concept of a ‘book’ differ from the Roman ‘liber’?

16. What were two characteristics of original Roman handwriting?

17. What was the first Roman province not on mainland Italy?

18. In which location did the Appian Way end?

19. What was the highest political office in the Roman Republic?

20. What caused the destruction in Pompeii and Herculaneum in AD79?

29.02.24: leaving the easiest to last; the accusative singular and plural of 2nd declension neuter nouns in -um

There is nothing to learn because the accusative singular and plural forms of neuter nouns in -um are exactly the same as the nominative singular and plural forms.

Nominative singular: templum

= Accusative singular: templum

Nominative plural: templa

= Accusative plural: templa

In urbe est templum antīquum. There's an old temple in the city.

> Templum antīquum vīsitāmus. We go to visit the old temple.

Hoc est pōculum. This is a drinking cup.

> Ūnum pōculum habeō. I have one drinking cup.

In urbe sunt multa templa antīqua. There are many old temples in the city.

> Multa templa antīqua in urbe vīsitāmus. We go to visit many old temples in the city.

Haec sunt pōcula. These are drinking cups.

> Tria pōcula habeō. I have three drinking cups.

29.02.24: practice with the accusative case

[1] Answer the questions in full sentences putting the words in brackets into the accusative singular.

Quem amās? [fīlius meus]

Quem amās? [fīlia mea]

Quid dēsīderās? [ūnus equus]

Quid habēs? [liber stilusque]

Quid vidēs? [taurus magnus] in agrō

Quem vidēs? [fēmina pulchra] in caupōnā

[2] Rewrite the sentences putting the words in brackets into the accusative plural.

Magister [puerī bonī] nōn castīgat.

[Multae puellae] in viā videō.

Agricola [duo equī] et [duae vaccae] habet.

Sextus [multī amīcī] in Ītaliā habet.

Magistra [discipulae bonae] amat sed [discipulī malī] nōn amat.

Quot [sacculī] portant servī?

malus, -a, -um: bad; evil; mischievous

29.02.24: the Appian Way

In the previous post, reference was made to the Via Appia, the Appian Way.

The Appian Way was the first and most famous of the ancient Roman roads, running from Rome to Campania and southern Italy. It was begun in 312 BCE and, at first, ran only 132 miles (212 km) from Rome south-southeastward to ancient Capua in Campania. However, by about 244 BCE it had been extended another 230 miles (370 km) southeastward to reach the port of Brundisium (Brindisi), situated in the “heel” of Italy and lying along the Adriatic Sea. From there Roman ships sailed to Greece and Egypt.

29.02.24: reading practice

Read and try to understand the text with the help of the vocabulary and with notes from previous posts.

[The Road to Latin (Chesnutt) 1932]

Cornēlius et fīliī

Cornēlius et fīliī in Viā Appiā sunt. Virum armātum vident. Vir armātus est nūntius Rōmānus et equum album habet. Et nūntius et equus sunt dēfessī quod Rōmam properant. Nūntius magnam pugnam Rōmānam nūntiat. “Ubi, mī amīce, Rōmānī pugnant?” clāmat Cornēlius. “Rōmānī in Galliā pugnant, Cornēlī,” respondet nūntius. “Quis est lēgātus?” rogat Cornēlius. “Rōmānī Labiēnum lēgātum habent,” respondet nūntius. “Labiēnus gladium tenet et virōs armātōs vocat. Tum virī armātī pugnant.” Nūntius Rōmam properat sed Cornēlius et fīliī domum ambulant. Lūcius nūntium et equum album laudat. Tum parvus Pūblius clāmat, “ego gladium magnum dēsīderō! Parvī puerī semper gladiōs dēsiderant.” “Lēgātī, mī fīlī, nōn parvī puerī, gladiōs habent,” respondet Cornēlius. “Gladium nōn dēsīderās, parve Pūblī,” clāmat Lūcius. “Tū es parvus puer. Ego sum paene adultus et gladium dēsiderō.” Marcus, meus fīlius adultus, gladium habet,” respondet Cornēlius, “sed vōs fīliī meī, nōn estis adultī et nunc librōs tabellāsque, nōn gladiōs, dēsīderātis.”

albus, -a, -um: white

armātus, -a, -um: armed

Gallia: Gaul

lēgātus: lieutenant; envoy

nunc: now

nūntiāre: announce; report

paene: almost

properāre: hurry; rush

pugna: battle

respondet: he / she replies

semper: always

tabella: writing tablet

tenet: he / she holds

tum: then

vident: they see

vocāre: to call; summon

Notes:

[i] Latin does not use a preposition when it refers to going to a named town; the accusative without a preposition is used:

Rōma: Rome > Rōmam properant: They are hurrying to Rome.

This also occurs with the noun domus:

Nūntius Rōmam properat sed Cornēlius et fīliī domum ambulant.

The messenger is hurrying to Rome but Cornelius and (his) sons are walking home.

[ii] nunc librōs tabellāsque ...dēsīderātis: look out for -que, an encltic word i.e. one which is attached to the word before it. It often occurs and means 'and': "Now you desire ... books and writing tablets."

[iii] Note the use of the vocative case: “Ubi, mī amīce, Rōmānī pugnant?” │ "Where, my friend, are the Romans fighting? Cornelius uses this case because he is addressing the messenger directly.

29.02.24: accusative singular and plural of second declension nouns in -us

[The Road to Latin (Chesnutt) 1932]

Read and try to understand the text using the vocabulary to help you.

Note the endings -um and -ōs: these are the singular and plural endings for the accusative of the second declension nouns in -us - and the endings are the same for the adjectives,

Cornēlius est dominus vīllae; dominus Cornēlius est vir bonus. Dominus bonus servum laetum habet. Puer laetus dominum bonum amat. Dominus magnum hortum habet; dominus et domina in hortō ambulant. Hortus est longus et lātus. Servus laetus in hortum properat. Ferē cotīdiē in hortō labōrat. Esne dēfessus, serve bone? Esne tū dēfessus, puer? Cornēlius multōs fīliōs habet. Fīliī sunt bonī. Fīliī sunt Marcus, Lūcius, Aulus, Pūblius, Servius. Fīliī parvī sunt Pūblius et Servius. Fīlius adultus est Mārcus. Estisne discipulī bonī, puerī? Lūcius est discipulus bonus et dīligenter labōrat. Aulus quoque est bonus discipulus. Fīliī parvī nōndum sunt discipulī. Cornēlius fīliōs bonōs amat et saepe laudat. Nōnne Cornēlium amātis, fīliī?

adultus, -a, -um: adult; grown-up

cotīdiē: every day; daily

dēfessus, -a, -um: tired

dīligenter: diligently; carefully (dīligenter labōrat: he / she works hard)

domina: mistress

dominus: master

dominus vīllae: master of the house (more on this in a later post)

ferē: almost

laetus, -a, -um: happy

lātus, -a, -um: wide

laudāre: to praise

nōndum: not yet

properāre: hurry

saepe: often

Note: Esne dēfessus, serve bone? │ Are you tired, good slave? The adjective in -us also has a vocative form; it's used here because the slave is being addressed directly.

The image shows the pater familias (paterfamilias), the oldest living male in the family and the head of the Roman household; he is pictured with his wife (uxor) and children (līberī).

29.02.24: The useless shopkeeper

The useless shopkeeper (tabernārius), but why is the shopkeeper not quite as useless as he first appears?

A: Salvē, tabernārie! [Why does tabernārius change to tabernārie?]

B: Salva sīs! Quid agis hodiē? [Is the customer male or female? How do you know?]

A: Optimē, grātiās tibi agō. Et tū?

B: Haud male. Quid desiderās?

A: Habēsne ūvās?

B: Minimē, ūvās nōn habeō. Ūvās in vīnētō habent. Quid aliud desiderās?

A: Ostreās desiderō.

B: Quot ostreās desiderās?

A: Duās ostreās desiderō.

B: Ostreās nōn habeō, sed multās ostreās in forō piscātōriō habent.

A: Habēsne fabās?

B: Minimē vērō, fabās nōn habeō! Fabās dēliciōsās in forō olitoriō habent.

A: Duās vaccās desiderō.

B: Esne insāna? Cūr mē rogās? Vaccās nōn habeō. Vaccās pulchrās in forō boāriō habent!

A: Cūr neque ūvās neque ostreās habēs? Cūr neque fābas neque vaccās habēs?

B: In tabernā librāriā es!

cūr: why?

desiderāre: to want; desire

hodiē: today

insānus, -a, -um: crazy; insane

quid aliud: what else?

rogāre: ask

tabernārius: shopkeeper

vīnetum: vineyard

29.02.24: accusative case plural of first declension nouns

Sometimes, a single and memorable phrase can be enough to have complete mastery over case endings. The image in the previous post gives you both the accusative singular and the accusative plural of first declension nouns:

Lūnam et stēllās spectāmus: We look at the moon and the stars

The accusative plural of first declension nouns is -ās:

Accusative singular:

Schola Rōmāna neque iānuam neque fenestram habet. The Roman school has neither a door nor a window.

> Accusative plural:

Schola Americāna et iānuās et fenestrās habet. The American school has both doors and windows.

Scholae magistram [accusative singular] et puellās [accusative plural] dēlectant. [Literally: The schools please the teacher and the girls] = The teacher and the girls like the schools.

And, as always, the same endings apply to the adjectives:

Schola antīqua longās sellās habet. The old school has long seats (benches).

Schola nova parvās sellās habet. The new school has small seats.

Schola Rōmāna puellās Americānās dēlectat … [Literally: the Roman school pleases the American girls] = The American girls like the Roman school.

Puellae Americānae scholās apertās amant. The American girls love open-air schools.

And while you’re looking at the moon and the stars, add two adjectives …

Lūnam candidam et stēllās pulchrās spectō. I look at the bright white moon and the beautiful stars …

... and you have the case endings!

[1] Practise saying who you love:

Quem amās? Who(m) do you love?

fīliae meae: my daughters > Fīliās meās amō. I love my daughters.

- amīcae meae

- magistrae meae

[2] Practise saying what you want in a shop by asking ‘do you have’: habēsne...?

ūvae: grapes > Habēsne ūvās? Do you have grapes?

- olīvae (olives)

- ostreae (oysters)

- fabae (beans))

[3] Practise saying what things you see in a house. And you see two things every time!

Quid in domō vidēs? What do you see in the house?

Duae mēnsae > Duās mēnsās videō. I see two tables.

- duae fenestrae

- duae iānuae

- duae sellae

- duae statuae

[4] And take a step further. How do you translate these sentences.

- Duās vaccās magnās in agrō videō.

- Duās mēnsās longās in scholā videō.

- Duās puellās parvās et trēs ancillās pulchrās In hortō videō.

- Multās puellās Americānās in pictūrā videō.

- Ūnam magistram Americānam in pictūrā videō. Why is it ūnam?

29.02.24: a single phrase can mean a lot

29.02.24: accusative case singular of first declension nouns

The accusative case allows you to be able to express yourself far more widely than you have done up to now. It has several uses, but the one on which we will focus is to indicate the direct object of the sentence. The direct object is the person or thing that the action is being done to e.g.

The maidservant is preparing dinner.

Maidservant is the subject of the sentence i.e. the person who is performing the action.

Dinner is the direct object of the sentence; it is what is being prepared i.e. the action is being done to it.

In English this is referred to as an S-V-O construction i.e. subject – verb – object

I (S) read (V) a book (O).

You (S) drink (V) wine (O).

The maidservant (S) is preparing (V) dinner (O).

In Latin, the direct object is in the accusative case.

Nouns in the first declension change the ending -a in the singular to -am:

cēna (dinner) > Ancilla (S) cēnam (S) pārat (V). The maidservant is preparing dinner.

Unlike English, the most common word order is S-O-V: Subject – direct Object – Verb. It is, of course, possible to change the words around in Latin since the endings make it clear who / what the subject and the direct object are, but it is the S-O-V words order that you will see most often.

Examples from the text posted below:

[i] Schola Rōmāna iānuam nōn habet. The Roman school does not have a door.

[ii] Antīqua schola fenestram nōn habet. The old school does not have a window.

And, as might be expected from the information in previous posts, the 1st / 2nd declension adjective has the same ending:

[iii] Schola Americāna mēnsam magnam habet. The American school has a large desk.

A phrase in the text which we will practise more occurs in:

[iv] Schola Rōmāna Iūliam et Cornēliam dēlectat. [Literally: the Roman school(S) pleases (V) Julia and Cornelia (O)] = Julia and Cornelia like the Roman school. Julia and Cornelia are in the accusative case because something pleases them i.e. they are the direct objects of the sentence.

[v] Schola antīqua (S) magistram Americānam (O) dēlectat (V). The same construction applies here: the literal translation is ‘The old school (S) pleases (V) the American teacher (O)’ = The American teacher likes the old school.

Practice

[1] An alternative way of saying ‘I have’ is to use the verb habēre (to have); habēre is a second conjugation verb, which we will deal with in detail soon, but we will use it here because what you have is in the accusative case:

Quid habēs? What do you have?

vīlla: a country estate > vīllam habeō: I have a country estate

Now practise the same construction with the following nouns:

- casa

- pecūnia

- taberna

- tabula

- vacca

[2] Similarly, the verb vidēre (to see) is second conjugation but can be used to practise the same construction:

Quid vidēs? What do you see?

fenestra: window > Fenestram videō. I see the / a window.

Now practise the same construction with the following nouns:

- iānua

- lucerna

- mēnsa

- pictūra

- schola

- sella

[3] Quem vidēs? Who(m) do you see? Quem is the accusative of quis and, in fact, the highest standard of English still shows an accusative case in the question word whom even if, nowadays, it is falling out of fashion.

discipula: pupil (f) > Discipulam videō. I see the / a pupil (f).

Now practise the same construction with the following nouns:

- amīca

- ancilla

- fīlia

- magistra

[4] And take that one step further with the same nouns above:

Discipulam meam videō. I see my pupil.

28.02.24: the accusative case (singular and plural) of first declension nouns

[The Road to Latin (Chesnutt) 1932]

These simple texts introduce you to a new case i.e. the accusative case; look at the endings in bold, try to understand both texts using the additional vocabulary, and, in the next post, the accusative case will be explained in detail.

SCHOLA RŌMĀNA I

Schola est schola Rōmāna. Parva est schola Rōmāna sed magna est schola Americāna. Schola Rōmāna iānuam nōn habet quod schola est aperta. Antīqua schola fenestram nōn habet quod schola nōn est tēcta. Antīqua schola mēnsam nōn habet. Schola Americāna mēnsam magnam habet. Schola antīqua magistram Americānam dēlectat. Schola Rōmāna Iūliam et Cornēliam dēlectat. Cūr schola antīqua magistram Americānam dēlectat? Schola antīqua magistram Americānam dēlectat quod schola est aperta.

SCHOLA RŌMĀNA II

Scholae magistram et puellās dēlectant. Antīqua schola Rōmāna est. Nova schola americāna est. Schola antīqua longās sellās habet. Schola nova parvās sellās habet. Schola Rōmāna neque iānuam neque fenestram habet. Schola Americāna et iānuās et fenestrās habet. Antīquae scholae sunt apertae; sed nova scholae sunt tēctae. Schola Rōmāna puellās Americānās dēlectat quod puellae Americānae scholās apertās amant.

antīquus, -a, um: old, ancient

cūr: why

dēlectat / dēlectant please(s); delight(s)

et . . . et: both . . . and

habet: has

habent: have

longus, -a, um: long

neque: and not, nor, neither

neque . . . neque: neither . . . nor

novus, -a, um: new, fresh, recent, modern

quod: because

Rōmānus: a Roman (man)

Rōmāna: a Roman (woman)

tēctus, -a, -um enclosed, covered

28.02.24: simple reading

[The Road to Latin (Chesnutt) 1932]

SCHOLA AMERICĀNA I

Schola est schola Americāna. Schola est magna. Iānua est clausa. Fenestra nōn est clausa. Fenestra est aperta. Mēnsa est magna. Sella nōn est magna. Sella est parva. Fēmina est Americāna. Fēmina est magistra. Magistra stat. Puella est Americāna. Puella magistra nōn est. Puella est discipula. Puella quoque stat. Puella est Iūlia. Iūlia discipula bona est. Cornēlia est discipula. Cornēlia quoque discipula bona est. Sella nōn est magna. Sella est parva. Mēnsa nōn est parva. Mēnsa est magna. Fenestra clausa nōn est. Fenestra aperta est. Iānua nōn est aperta. Iānua est clausa.

SCHOLA AMERICĀNA II

Iūlia est discipula. Cornēlia est discipula. Discipulae sunt Iūlia et Cornēlia. Puellae Americānae sunt discipulae. Discipulae bonae sunt. Discipulae stant. Magistra quoque stat. Scholae Americānae sunt magnae. Fenestrae magnae sunt et iānuae parvae sunt. Iānuae sunt clausae sed fenestrae sunt apertae. Discipula bona est. Cornēlia est discipula. Cornēlia quoque discipula bona est. Sella nōn est magna. Sella est parva. Mēnsa nōn est parva. Mēnsa est magna. Fenestra clausa nōn est. Fenestra aperta est. Iānua nōn est aperta. Iānua est clausa.

apertus, -a, -um: open

clausus, -a, -um: closed

28.02.24: numbers 11-20

Step-by-step: maybe you’re 51 years and six months old, but, for the moment, you have full license to tell lies! Here, we focus on saying your age and the ages of others. Read the dialogues and note the phrases in bold.

Quid nōmen tibi est?

Nōmen mihi Mārcus est?

Esne in Ītaliā nātus?

Minimē, in Hispāniā nātus sum.

Quot annōs nātus es?

Ūndecim annōs nātus sum.

____________________

Quid nōmen tibi est.

Nōmen mihi Iūlia est.

Habitāsne in Ītaliā?

Ita, puella Rōmāna sum. In Ītaliā habitō.

Quot annōs nāta es?

Vīgintī annōs nāta sum.

____________________

Quis est hic?

Hic est amīcus meus.

Quid nomen eī est?

Nōmen eī Mārcus est.

Estne Rōmānus?

Ita vērō, Rōmānus est.

Quot annōs nātus est?

Septendecim annōs nātus est.

____________________

Estne tibi fīlius?

Ita vērō, mihi fīlius est.

Quid eī nōmen est?

Nōmen eī Iūlius est.

Quot annōs nātus est?

Quīndecim annōs nātus est.

____________________

Estne tibi fīlia?

Sīc, mihi est ūna fīlia. Fīlia mea tredecim annōs nāta est.

You have already seen nātus (masc.) and nāta (fem.) when talking about where you were born.

In Asiā nātus / nāta sum. I was born in Asia.

The same construction is used when talking about ages. You also need a form of the noun annus (year); why it is written in a different form i.e. annōs, you will learn later; simply familiarise yourself with the phrases.

Quot annōs nātus (masc.) / nāta (fem.) es? [literally: For how many years have you been born?] = How old are you?

Decem annōs nātus (masc.) / nāta (fem.) sum. [literally: I have been born for ten years.] = I am ten years old.

Quot annōs nātus (masc.) / nāta (fem.) est? How old is he / she?

Fīlius meus duodecim annōs nātus est. My son is 12 years old.

Fīlia mea sēdecim annōs nāta est. My daughter is 16 years old.

The numbers 11-20 (and that is all that we will do here) are formed:

[i] for 11 -17: from the numbers 1-7 + decim (not decem); note that there are some spelling changes in 1-7 when they are added to decim

11: ūndecim

12: duodecim

13: tredecim

14: quattuordecim

15: quīndecim

16: sēdecim

17: septendecim

[ii] for 18-19: the numbers are in three parts although written as one word

duodēvīgintī i.e. duo ¦ dē ¦ vīgintī (literally: two ¦ from ¦ twenty) = 18

ūndēvīgintī i.e. ūn¦dē¦vīgintī (literally: one ¦ from ¦ twenty) = 19

Note: the numerals octōdecim and novemdecim for 18 and 19 do exist, but they are very rare; you should stick to the Classical forms above for these two numbers.

[iii] 20: vīgintī (French: vingt; Spanish: veinte)

The Roman numeral forms in the image are easy to interpret: they are simply X (10) with the numerals for 1-9 added to them e.g.

X + I (10 + 1) = XI = ūndecim = 11

28.02.24: introduction to adjectives

[refer to images: A New Latin Primer (Mima Maxey (1933)]

The text is simple enough, but focus on the words in bold.

Haec est magistra.

“Salvēte, discipulī, puerī et puellae.”

Puer est discipulus.

Puella est discipula.

Hae sunt discipulae.

Hī sunt discipulī.

Haec est puella.

Magistra nōn est puella.

Magistra est fēmina.

Haec est magistra. Haec est fēmina. Haec est puella. Haec puella est discipula. Haec puella nōn est magistra.

Haec puella est parva. Haec puella nōn est parva; haec puella est magna.

Haec puella nōn est parva; haec puella est alta.

Haec puella est bona. Fēmina quoque est bona.

Haec puella nōn est bona.

Haec puella est magna. Magistra quoque est magna.

Haec puella est parva.

Puella est pulchra quoque.

quoque: also

alta, bona, magna, parva, pulchra

These words are adjectives i.e. they are used to describe a person or thing. There is, in fact, nothing new to learn here since this type of adjective has the same endings as meus etc.

masculine: altUS (tall)

feminine: parvA (small)

neuter: magnUM (big)

They all end in -a in the text because a girl is being described. However, below are examples with all three genders:

discipulus bonus: a good pupil (masc.)

discipula bona: a good pupil (fem.)

vīnum bonum: good wine (neut.)

These adjectives are known as first / second declension adjectives because they have the same endings as first / second declension nouns.

pulchra (beautiful) belongs to the same group but look at its masculine form:

pulcher

It is the same as a second declension noun in -er (e.g. like magister) and, like the noun, loses the /e/ before the ending is added:

pulcher (masc.)

pulchra (fem.)

pulchrum (neut.)

Adjectives can be [i] attributive or [ii] predicative:

[i] an attributive adjective in English precedes the noun:

a beautiful temple

[ii] a predicative adjective follows the verb 'to be'

the temple is beautiful

[i] In Latin, the attributive adjective, as most often occurs in French, follows the noun although, given the flexibility of Latin word order, this is not a hard and fast rule

templum pulchrum: a beautiful temple

[ii] The predicative adjective in Latin follows the verb:

Templum est pulchrum: the temple is beautiful

However, again, given the word order of Latin, the same concept can also be expressed as:

Templum pulchrum est.

The plurals of these adjectives you already know since they are exactly the same as 1st / 2nd declension nouns:

discipulus bonus: a good pupil (m)

> discipulī bonī: good pupils (m)

puella parva: a little girl

> puellae parvae: little girls

templum pulchrum: a beautiful temple

> templa pulchra: beautiful temples

Therefore, based on what you now know about 1st / 2nd declension adjectives, explain the endings in bold:

- Servus in hortō magnō labōrat.

- Amīcus meus in vīllā magnā habitat.

- Agricola in casā parvā habitat.

- Sacerdōs in templō magnō ōrat.

- In armāriō parvō sunt armillae et annulī.

28.02.24: learning by practising

Learning a language – any language – will not be achieved by merely staring at grammatical tables. Actively practising concepts will help you absorb the concepts. Look at [i] the sentence patterns in image #1 and [ii] the exercise in image #2. Now, it is unlikely that you’ll ever be buying a sword in an ancient Roman market, but that’s not the point. The aim is to make you think about the endings that are needed, and, by verbalising them in the form of practical questions, to help you remember them. Furthermore, the vocabulary used is essential at this elementary stage of learning Latin and so, by saying the words, you will remember the vocabulary too. These are not tests; if you cannot recall something, then the exercises provide you with the impetus to look back through these posts, or to consult other references.

27.02.24: paying attention; similarities in case endings

If your aim is to read Latin (and to speak it) with any degree of precision, then it is vital to learn the endings as you go along – slowly and thoroughly. Below is some more information on quis and hic, haec and hoc which show [i] subtle changes in endings and [ii] that the endings of Latin words can serve more than one function. Look in particular at the words in bold.

Quis est hic vir? Who is this man?

> QUĪ sunt hī virī? Who are these men? [masculine nominative plural of quis?]

Quis est HAEC fēmina? Who is this woman?

> QUAE sunt hae fēminae? Who are these women? [feminine nominative plural of quis?]

Quid est hoc aedificium? What is this building?

> QUAE sunt HAEC aedificia? What are these buildings? [neuter nominative plural of quid?; this is the same as the feminine nominative plural; haec is the nominative plural of hoc; this is the same as the feminine nominative singular]

[i] The first image below summarises the forms of quis?

[ii] The second image shows the differences with masculine and feminine nouns.

[iii] The third shows the use of the neuter haec:

QUAE sunt HAEC arma? What are these weapons? The word ‘arma’ is neuter plural; the speaker does not know what these arms are, but when the answers are given, the genders are known and so hic, haec and hoc agree in the plural.

A useful way of remembering the neuter singular and plural forms quid / quae is by comparing one method of asking the names of more than one person:

nōmen (neuter): name

Quid est nōmen eius? What is his / her name?

Quae sunt nōmina eōrum? What are their (m) names?

Quae sunt nōmina eārum? What are their (f) names?

27.02.24: topical vocabulary [5] things around you (in the street and in the town)

[1] Quid est in viā tuā? What’s in your street?

In viā meā est pavīmentum. On my street there’s a pavement.

pavīmentum: refers to a floor composed of stones that have been beaten down rather than, specifically, a raised walkway either side of the street. The separate image, however, does show that, in Pompeii, there were raised walkways.

Smaller than a via is sēmita, which is a footpath or a lane.

In viā meā est thermopōlium. …a hot food outlet

In viā meā sunt multae tabernae. In my street are many shops.

[2] Quid est in oppidō tuō? What’s in your town?

Note: the word for ‘city’ is urbs, a feminine noun which is not a first or second declension noun. If you use it, then note the difference: Quid est in urbe tuā? In urbe meā est / sunt … What’s in your city? In my city there is / are …

In oppidō meō / in urbe meā est fluvius. In my town / city there is a river.

In oppidō meō est ludus. … a school

ludus: can refer to school, or, specifically, a gladiator school; the word schola also can be used to refer to a school. The image shows the remains of the gladiator school next to the Colosseum in Rome.

In oppidō meō est circus. … a racecourse; the most famous racecourse was the Circus Maximus

In oppidō meō est unum amphitheātrum. ...one amphitheatre

In oppidō meō est castrum. … a castle

castrum: You will see this word far more often in the plural i.e. castra to mean a military camp

In oppidō meō sunt multa templa. In my town there are many temples.

In oppidō meō sunt lātrīnae. …toilets

lātrina: toilet; the image posted shows that public toilets were far more ‘public’ than we would have liked.

In oppidō meō sunt thermae. …baths

thermae are public baths; the image shows the Roman baths in the aptly named English city of Bath

In oppidō meō sunt moenia …walls

moenia: refers to the defensive walls of a city, an important word to know since the Romans seemed to be constantly attacking or defending them.

27.02.24: topical vocabulary [4] talking about things around you (in the lounge, in the bedroom)

[image #1]

[1] Quid est in atriō tuō? What’s in your ‘lounge’?

We cannot really equate our concept of ‘lounge’ with the Roman ātrium, which was a large, impressively decorated entrance hall to where guests would be led in order to meet the paterfamilias, the head of the household; they were wealthy and influential men, and would be regularly visited by their clientes, people who sought their assistance either financially or in the hope that the master of the house would do favours for them.

In atriō meō est ōstium. In my lounge there’s a door

iānua: generally referred to the first entrance to the house through which one entered from the street

ōstium: an inner door as opposed to the street door

The entrances to bedroom were sometimes closed off by a curtain (vēlum).

The image posted separately shows the reconstruction of the outer and inner door of a Pompeian house.

In atriō meō est statua. In my lounge there’s a statue

In atriō meō sunt duae fenestrae. In my lounge there are two windows.

In atriō meō sunt lucernae. … (oil) lamps

In atriō meō sunt pictūrae. … pictures / paintings

In atriō meō sunt quattuor sellae. … four chairs

[image #2]

[2] [i] Quid est in cubiculō tuō? What’s in your bedroom?

In cubiculō meō est lectus. In my bedroom there’s a bed

lectus: bed; couch; sofa; a synonym for lectus is strātum which can also refer to a bed covering

In cubiculō meō est armārium. …a cupboard

In cubiculō meō sunt cunabula. In my bedroom there’s a cradle.

cunabulum: cradle normally occurs as a plural, hence cunabula; the disturbing image posted separately shows the baby cradle found in Pompeii, and the remains of the baby were found inside it

[ii] Quid est in armāriō tuō? What’s in your cupboard?

In armāriō meō est pecūnia. In my cupboard there’s money

In armariō meō sunt ānullī et armillae: In my cupboard are rings and bracelets

[iii] Quid est in lectō tuō? What’s on your bed?

In lectō meō sunt pulvīnī. On my bed are pillows.

27.02.24: topical vocabulary [3] talking about things around you (in a garden, on a farm)

[1] Quid est in hortō tuō? What’s in your garden? [image #1]

In hortō meō est castanea. In my garden there is a chestnut tree

In hortō meō est herba. …grass

In hortō meō sunt plantae. In my garden there are shrubs.

In hortō meō sunt bācae. …berries

In hortō meō sunt ūvae. …grapes

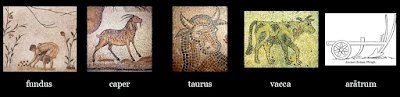

[2] Quid est in fundō tuō? What’s on your farm? [image #2]

In fundō meō est taurus. On my farm there’s a bull.

In fundō meō sunt vaccae. On my farm there are cows.

In fundō meō sunt equī et caprī. …horses and goats

In fundō meō sunt tria plaustra et ūnum arātrum. … three wagons and one plough

27.02.24: topical vocabulary [2] talking about things around you (in a bag, in a kitchen, in a study)

Look around your room. What do you see?

liber: a book

fenestra: a window

iānua: a door

mēnsa: a table

sella: chair

You may not know a lot yet, but you can still organise vocabulary according to topics: you can head separate pieces of A4 and add the vocabulary based on the headings, or you can do the same on your laptop. The next few posts will focus on acquiring a handful of words for different topics.

There is an important point to note: Classical Latin language and the culture and way of life of Ancient Rome cannot always convey modern ideas. Look at this question: ‘Quid est in ātriō tuō?’ This is the closest we can come to the English equivalent of ‘lounge’ or ‘sitting room’ since Roman houses were not constructed in the same manner as houses are constructed now. However, the question is still valid since it refers to that large (and impressively decorated) area of the house where, for example, guests would be welcome. Similarly, the Romans did not have pens and pencils as we understand them, but, when responding to the question ‘Quid est in sacculō tuō?’ (What’s in your bag?), it is also reasonable to refer to items that the Romans did use for those purposes e.g. stilus, tabula.

‘New Latin’ i.e. vocabulary developed to meet 21st century needs, does exist: there is, for example, a ‘Latin’ word for motorcar (autoraeda), and those words can be found in, for example, online dictionaries, but the aim of this course is to develop the vocabulary of Classical Latin as it was used by the Roman authors. Therefore, if you desperately want to say that your room has air conditioning, you will either need to find the New Latin for it (which is generally beyond the scope of these posts) or simply say that it has a window!

From time to time, words which were in Classical Latin but, to serve contemporary communication, have had meanings added to them, will be referred to since their original meanings are still important to know.

If you want to branch out on your own and look for New Latin words, then you can consult:

[1] Quid est in sacculō tuō? What’s in your bag?

In sacculō meō est liber. In my bag there’s a book.

As you have already seen, meus and tuus have the same endings as first and second declension nouns. Here, they are in the ablative singular, used with the preposition ‘in’.

[2] Quid est in culīnā tuā? What’s in your kitchen?

In culīnā meā sunt pōcula. In my kitchen there are drinking cups.

[3] Quid est in scriptōriō tuō? What’s in your study?

In scriptōriō meō est librārium. In my study there’s a bookcase.

Let’s look at these three questions and include some vocabulary that are related to the topics.

[1] Quid est in sacculō tuō? [image #1]

sacculus: a small bag, satchel (in New Latin, this means ‘backpack’); the Roman poet Catullus invited his friend to dinner and promised him a sumptuous meal – provided the friend brought everything because Catullus himself had no money!

nam tuī Catullī plēnus sacculus est arāneārum

for the little purse of your Catullus is full of cobwebs

The other word that refers to a similar item is loculus, literally meaning ‘a little place’ and used in various senses, one of which was ‘satchel’; the image posted shows an example of a loculus on Trajan’s column in Rome.

In sacculō meō est papȳrus. In my bag there is paper

In sacculō mea est penna. …a pen

penna: feather, but feathers were used in making quills dipped in ink i.e. the predecessor of our modern pen

In sacculō meō est rēgula. … a ruler

In sacculō meō sunt duo librī. In my bag there are two books

In sacculō meō sunt multī calamī / stilī …many pens

calamus: a type of sharpened, split reed pen used for writing in ink on papyrus or parchment in ancient times

In sacculō meō sunt multī stilī plumbātī … many pencils

stilus plumbātus: (New Latin); you have already seen stilus many times referring to the thin pointed metal instrument used for writing on wax tablets. ‘plumbātus’ from the verb ‘plumbāre’ (to make with lead) means ‘made of lead’ and so the phrase does convey the idea of a pencil, even though the Romans didn’t have them!

[2] Quid est in culīnā tuā? What’s in your kitchen? [image #2]

In culīnā meā est furnus. In my kitchen there is an oven.

In culīnā meā sunt caccabī. In my kitchen there are cooking pots.

In culīnā meā est mēnsa. In my kitchen there's a table.

Quid est in mēnsā tuā? What’s on your table?

In mēnsa meā est cibus. On my table there’s food.

In mēnsā meā sunt multa pōcula. On my table there are many drinking cups.

In mēnsā meā sunt catillī et cultrī. … plates and knives.

catinus: a large bowl, dish, or plate

catillus: a smaller version (i.e. a diminutive form) of the same things

The challenge of conveying our modern concepts is well explained by William Smith in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities:

"catinus or catinum, dim. catillus or catillum, a dish or platter on which viands were served up. Other names for similar table utensils will here be noticed; but it must be admitted that the differences of shape, materials, or use are not always clearly indicated. Even the distinction, so essential to our notions, between dishes and plates does not seem to have been observed … there is in fact no Greek or Latin word for “a plate” in the modern sense."

[3] Quid est in scriptoriō tuō? What’s in your study? [image #3]

scriptōrium: a room where writing took place

In scriptoriō meō est capsa. In my study there is a ‘capsa’.

capsa: a cylindrical container used for holding scrolls

In scriptoriō meō est librārium. … a book case

In scriptoriō meō est ātrāmentum. In my study there’s ink.

In scriptoriō meō sunt litterae. In my study there are letters.

litterae: the singular (littera) refers to a letter of the alphabet, whereas the plural (litterae) refers either to one or more letters i.e. written communication; the plural also refers to ‘literature’

An alternative to litterae is epistula, which refers to a single written communication: epistula (a letter) > epistulae (letters)