There are two points in this text which are “knocking at the door” of Level 3, one of which was briefly discussed in an earlier post and one which has never been discussed at all; both involve a longer explanation than is given here, but we can at least begin to look at them; they both matter because they both very frequently occur. We’ll deal with the first one in this post, and the second one in the next post.

the ablative absolute

Take a look at these two sentences:

[i] After killing / having killed the traitor, the commander

sent envoys to the camp.

In [i] it was the commander who killed the traitor

[ii] The traitor having been killed, the commander

sent envoys to the camp.

In [ii] the commander did not kill the traitor or, to be

more precise, that is not what is suggested i.e. the phrase in italics is not

connected to the subject of the sentence.

We are looking at [ii].

To express [ii] Latin uses a construction called the ablative

absolute and it occurs all the time in the literature; it refers to an event

that has / had happened to someone / something before the action in the clause;

the phrase stands alone, a “self contained” event which is detached from

the rest of the sentence: detached = Latin absolūtus

This is formed primarily with a noun + a participle but

other word types can be used; here, we are looking only at the noun + perfect

passive participle:

[i] prōditor (noun): traitor + interfectus (perfect passive

participle): (having been) killed

- prōditor interfectus │ a killed traitor / a traitor (having been) killed

[ii] Both parts are now put into the ablative case:

- prōditōre interfectō [= ablative absolute], dux lēgātōs ad castra mīsit.

[iii] The standard “grammar book” way of translating this

is:

- with X ¦ having been Y-ed

- with the traitor ¦ having been killed

That shows precisely what the phrase conveys. However, we

would rarely translate it that way.

[1] The following could translate the phrase in italics:

- The traitor having been killed, the commander sent envoys to the camp.

- After / once / when the traitor had been killed, the commander sent envoys to the camp.

None of those translations suggest the commander did it.

[2] The following do not translate the phrase in bold:

- Having killed the traitor, the commander …

- After he had killed the traitor, the commander …

Those two state that the commander himself killed the

traitor, and this is not what the Latin phrase is saying. What the Latin

says is that the traitor had been killed before the commander

sent envoys; there is no suggestion that the commander had anything to do with

it.

Could it be translated as [2] above? Yes, it possibly could

but only if the context is clear that it was the commander who had killed the

traitor e.g. if that had been stated in a previous sentence. At this stage, however,

it is best to stick to the translation versions in [1].

Here is a further example:

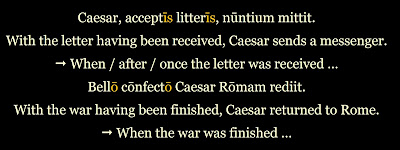

Caesar, acceptīs litterīs, nūntium mittit.

[i] litterae (noun): letter + acceptae (perfect passive

participle): (having been) received

- litterae acceptae │ a letter (having been) received

[ii] both parts in the ablative case

- litterīs acceptīs = ablative absolute

- (With) the letter having been received, Caesar sends a message.

- After / once / when the letter was received, Caesar sends a message.

Here are the examples from the original text:

[1] arma habemus non adversus eam aetatem, cui etiam captis

urbibus parcitur

[i] noun + perfect passive participle:

capta (perfect passive participle): (having been) captured +

urbs (noun): city

- urbs capta │ a captured city

- urbēs captae │ captured cities

[ii] both noun and participle put in the ablative

case:

captīs urbibus = ablative absolute

- (with) cities having been captured

- after / when / once cities have been captured

arma habemus non adversus eam aetatem, cui etiam captis

urbibus parcitur │ We do not use our weapons against those of an age which is

spared even when cities have been captured

[2] … deinde eum manibus post tergum inligatis

… pueris tradidit

[i] manūs (noun): hands + ligātae (perfect passive

participle): tied │ tied (bound) hands

- manūs ligātae │ tied hands

[ii] both noun and participle put in the ablative case:

manibus ligātīs = ablative absolute

- (with) his hands having been bound

- after / when / once his hands had been bound;

… deinde eum manibus post tergum inligatis …

pueris tradidit │ He then handed the man, with his hands tied behind his

back / his hands having been tied behind his back, over to the boys

There will be more on this later but I think that’s enough

to get the idea and get started. It will come up again and again.

The video goes into this in a little more depth if you do

want to find out more at this point.