Sphera terrestris …dīvīsa est in trēs continentēs; nostram, quæ subdīviditur in Eurōpam, Asiam, & Āfricam, in Americam (cuius incolæ sunt antipodēs nōbīs) & in Terram Austrālem, adhūc incognitam. (Comenius CVII: 1658)

The terrestrial sphere … is divided into three continents,

ours, which is subdivided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America, (whose inhabitants

are antipodes to us;) and the South Land, yet unknown.

antipodēs from Greek: ἀντίποδες

(antípodes), referring, in the world of Comenius, to the place on the opposite

side of the Earth from a given point, the English derivative antipodean

being an informal reference to the inhabitants of Australia and New Zealand,

but Comenius uses it to describe America.

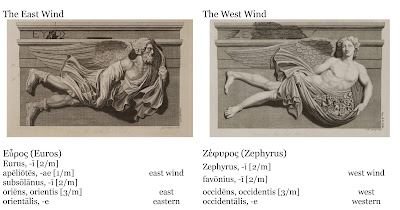

Images #1 and #2

[i] terra austrālis nōndum cognita (1570 (the southern land not

yet known)

[ii] terra austrālis incognita (1618) (the unknown

southern land)

However, the maps do not refer to Australia but to an as yet undiscovered (or partially discovered), unknown (or not yet known), disputed and, at times, dismissed notion of a landmass in the southern hemisphere, which was first suggested by Aristotle in the 4th century BC. And it did take a little time to prove that he was right!

What

we call the continent of Australia was originally named New Holland, the term Terra

Austrālis reserved for the southern landmass referred to above.

The English explorer Matthew Flinders was the first to

circumnavigate New Holland in 1803, and used the name ‘Australia’ to describe it

on a map in 1804. It was Flinders who suggested the name now used, the New

South Wales Governor Lachlan Macquarie endorsing the name to replace New

Holland in communication with London in 1817, and the name came into common

local usage.

Image #3: Map of Australia by Flinders (1814) ascribing the

name Terra Austrālis or Australia

On the “reassignment” of the name Terra Austrālis Flinders

wrote:

“There is no probability, that any other detached body of

land, of nearly equal extent, will ever be found in a more southern latitude;

the name Terra Australis will, therefore, remain descriptive of the

geographical importance of this country, and of its situation on the globe: it

has antiquity to recommend it; and, having no reference to either of the two

claiming nations, appears to be less objectionable than any other which could

have been selected.”

Flinders was, of course, wrong in making that bold assertion

because the “unknown southern land” did become known, by which point, however, the

name now belonged to Australia.

Maybe from the 4th century BC we hear Aristotle’s

voice telling Flinders: “I told you so!” Moreover, Aristotle had already given

it a name since, at the time, the north lay under the constellation Ἄρκτος [Árktos] i.e.

“Ursa Major” (the Great Bear). Therefore, he called the other end of the world ἀνταρκτικός [antarktikós]

i.e. opposite to the north > Latin: antarcticus, -a, -um (south) > New

Latin …

“The five largest islands or peninsulas … are termed continents, and designated by the names Eurasia, Africa, North America, South America, and Australia. …. The elevated region round the South Pole is crowned by the unexplored and scarcely discovered continent of Antarctica.” [Hugh Robert Mill, “The Continental Area” (1891)]