iste, ista, istud

This is a classic example of why you can spend a lot of time pondering about some aspect of Latin grammar, until it finally dawns on you that you don’t really need to.

From Wiktionary, and we’ll go from there:

Iste, ista, istud “… is used to refer to a person or thing,

or persons or things, near the listener. It contrasts with hic

(“this”), which refers to people or things near the speaker, and ille (“that”),

which refers to people or things far from both speaker and listener.”

In the previous post we looked at hic and ille

[1]

How much is this book? [The book is right in front of you or

maybe it’s in your hand.]

This is a big problem. [It’s as if the problem is before

your eyes.]

i.e. this and these are ‘close’ to you

Latin: hic, haec, hoc

hic liber: this book

[2]

How much is that book? [The book is maybe on a shelf in the

store and you’re pointing to it].

I love that part of the city. [You’re refering to something

that exists but not physically there when you speak.]

i.e. that and those are away from you and from the person

you’re talking to.

Look at that mountain. [Neither the speaker nor the person

being addressed are near it.]

Latin: ille, illa, illud

ille liber: that book

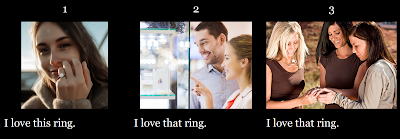

image #1: people talking about a ring

[1] and [2] are straightforward

[1] I love this ring (it’s on my finger and I’m showing it

to you): hic, haec, hoc

Hunc ānulum amō.

[2] I love that ring (that’s in the window away from both of

us): ille, illa, illud

Illum ānulum amō.

[3] It’s the third part of the image that we need to take a

look at. She likes the ring that’s on her friend’s finger i.e. what she is

referring to is close to the person she’s addressing. She isn’t pointing to

something that is distant from both of them.

English has no set rules for this but, sometimes, we like to

be specific in referring to something that is close to the

person you’re talking to.

That necklace looks really good on you. [He’s not referring to a necklace that’s in a shop window]

Let me take a look at that email you’re printing. [She’s not referring to an email that’s close to the person being spoken to]

[i] [image #2] Latin: iste, ista, istud: ‘that (person/thing)’; istī, istae, ista: ‘those (people/things)’

It has the same English translation as ille in the previous post, but it refers to a noun near the listener or connected to the listener. It is, therefore, sometimes known as the demonstrative of the second person because it refers to a noun near the person being directly addressed.

I love this restaurant. And do you see that waiter over

there? He’s from France. By the way, I love that watch. Did you get it for your

birthday?

That pupil of yours is always polite. [I’m

not talking about any pupil, but one who is associated with you i.e.

I am thinking about your pupil]

dē istīs rēbus exspectō tuās litterās

(Cicero) │ I’m waiting for your letter about affairs where

you are (translations vary but the idea is conveyed)

[ii] However, an important point about iste which

makes it stand out from ille you can first see in a possible

translation of it:

“What are you going to do about that son of yours?”

“That car of yours is always breaking down.”

Iste can be used negatively in Classical Latin,

to show disdain for a person or situation. Ille does

not convey that.

istae minae (Livy) │ those threats

(of yours)

A quick translation of that phrase in context shows its

negativity:

“and will you threaten the commons? will you threaten the

tribune? What, if you had not already twice experienced how little those

threats availed against the united sense of the people?”

Just focus on iste, look at the English context

and you can see why it’s being used. Also, the translator sometimes conveys it.

quae est ista praetūra? (Cicero) │ What

sort of a partnership is that of yours? (You take away a man's

inheritance, …)

tamen istum condemnētis necesse est

(Cicero) │ …, still you must condemn him (for it is not

permitted to us with impunity to rob one man for the purpose of giving to

another.)

quid quod adventū tuō ista subsellia

vacuēfacta sunt │ What of this, that upon your arrival those benches around

you / where you’re sitting were emptied,

Quid istud est negōtī? (Plautus) │ What

matter is this?

Think about a similar idea may be expressed: “What’s

all this / that about?” To express a

negative tone, an English speaker would stress the word. “Who does he

think he is?”

Here’s one from Plautus. English context …

“…he, together with his own son, is carousing with one

mistress the livelong day, and that he's secretly pilfering from her.”

ego istud cūrābō. │ I’ll take care of that.

Again, an English speaker would stress it with the implication there is some

problem.

Three points to take away from all of this:

[1] Whether you see forms of ille or iste,

both of them can be translated the same way

ille vir / iste vir: that man

illa femina / ista femina: that woman

Context would determine whether, in translation, the

negativity of iste / ista should be conveyed:

iste vir: that (wretched) man

ista fēmina: that (dreadful)

woman

illam amo: I love her

but …

istum odi: I hate him; I hate that

guy

[2] By Mediaeval times, there was no distinction in the use

of ille and iste, and iste had

lost its pejorative sense.

Two lines from the same song, and both mean the same:

bibit ille bibit illa │ he is

drinking, she is drinking

bibit ista bibit ille │she is

drinking, he is drinking

[Image #3] from another song in the same period:

Istud vinum, bonum vinum │ this wine,

good wine

[3] The other interesting aspect of ille and iste is

the way in which they “settled” into specific roles within the Romance

languages derived from Latin. Below are some examples.

La: ille > French le [i] the [masc.

sg.], and [ii] him

La: ille > French il: he

La: illa > French elle: she

La: illa > French la [i] the [fem. sg.],

and [ii] her

La: illōs / illās > French les [i] the

[pl.], and [ii] them

La: ille > Spanish [i] el: the, and [ii]

él: he

La: illa > Spanish [i] la: the, and [ii]

ella: she

La: illōs > Spanish los: the [masc. pl.]

La: illās > Spanish las: the [fem. pl.]

La: iste > Spanish este: this [masc. sg.]

La: ista > Spanish esta: this [fem. sg.]

La: istud > Spanish esto: this [neut. sg.]

You can see that some of them retained original Latin

meanings, but in both languages, and in other Romance languages, you see how

some of the original Latin words became definite articles i.e.

‘the’. In Classical Latin, however, there was no definite article; ille was

not used to express "the".

No comments:

Post a Comment