Some features of Latin grammar are far more important than

others. This one is fairly minor, but still needs to be recognised and known.

When young learners are becoming familiar with, for example,

plurals, they will normally start with friend(s), house(s), pen(s) and so on.

Then, as youngsters, they will generally and unquestioningly learn man > men

(Anglo-Saxon menn), sheep > sheep (Anglo-Saxon: sċēp; singular and plural)

child > children (Anglo-Saxon ċildru ) i.e. these nouns come from a

different declension pattern in Old English and have retained their

plural forms. A five-year-old, however, isn’t that concerned about why ‘child’

becomes ‘children’, but you may be curious about why he said Hustoniae habitō in

the video.

Hustoniae habitō: I live in Houston

When we say in a place or on a

place in Latin, we use in + ablative:

In argentāriā labōrō. I work in a

bank.

Liber meus in mēnsā est. My book is on the

table.

Mārcus in hortō sedet. Marcus is

sitting in the garden.

However, the form being used in the video is the locative

case. This case did exist in Latin but finally merged with the ablative

although, in some instances, an old locative case ending still appears. If you

look up the tables of nouns in, for example, wiktionary, no locative

form will be listed unless the noun in question has one.

[i] There is a handful of nouns that have a

locative; the examples that are most common and most quoted in grammar books

are listed below, and one of them you have already seen. No preposition

is used; the case ending alone conveys the idea of being at / in / on a

place.

domus: house > domī: at home e.g. Mārcus domī est. Marcus

is at home.

humus: ground > humī: on the ground e.g. Humī sedent.

They’re sitting on the ground.

bellum: war > bellī: in battle

Valēte, iūdicēs iūstissimī, domī, bellīque, duellātōrēs

optimī (Plautus) ¦ Fare ye well, at home, most upright judges, and in

warfare most valiant combatants.

rūs: countryside > rūrī: in the countryside

In the video he referred to “in nātūrā” (in nature; in the

natural world) but, if he’d said that he liked to go for a walk “in the

countryside”: Mihi perplacet rūrī dēambulāre” i.e. rūrī has its

own locative ending to express the idea.

[ii] The locative is used with the names of “cities, towns

and small islands”; that’s the standard answer! With cities and towns, it’s

clear:

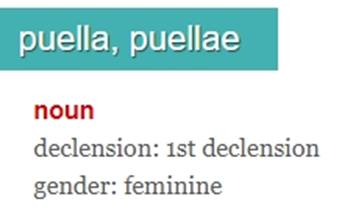

Rōma: Rome > Rōmae [the ending is the same as the

genitive singular]: in Rome; you don’t say *in Rōmā*

Lutetia: Paris > Lutetiae: in Paris

Hustonia (New Latin): Houston > Hustoniae: in

Houston

Corinthus: Corinth [the ending is the same as the genitive

singular] > Corinthī: in Corinth

Londinium: London > Londiniī: in London

Eborācum: York > Eborācī: in York

Brundisium: Brundisium (Brindisi) > Brundisiī: in

Brundisium

Pliny writes of his uncle:

Erat Mīsēnī classemque imperiō praesēns regēbat. ¦ He

was at Misenum and was personally commanding the fleet.

Some place names in Latin are plural; their locative forms

are the same as the ablative and so the only point you have to remember is that

they don’t use prepositions

Athēnae: Athens > Athēnīs: in Athens e.g. Athēnīs nātus

est. He was born in Athens.

Pompeiī: Pompeii > Pompeiīs: in Pompeii

There’s a bit more – only a bit – that needs to be talked

about with regard to these, but I think that’s enough for the moment to explain

why he said Hustoniae habitō in the video. The key point

to remember is that when you say in a named town or city, a

locative case with no preposition is used.

** What is written below is more for interest and to show

that, when studying Latin, there will be points which are not absolutely clear

or consistent. They’re not of crucial importance. **

How do you define a small island? It’s a

neat phrase to remember that the locative is used with the names of “towns,

cities and small islands”, it trips off the tongue and it trips off

the page of every grammar book you pick up, most of those books tending to

avoid further discussion on the matter. And when writers on Latin are avoiding

discussion, that suggests not all is quite what it seems!

It’s a small point but it’s a good example of looking at the

language in slightly greater depth and using the authors for reference.

Does English distinguish between large and small islands in

the way that the Romans did? Britain is an island and so is Ireland, and we

would say in Britain (La. in Britanniā) and in Ireland

(La. in Hiberniā) i.e. large land masses with very many settlements,

but when the island gets smaller – sometimes with one or very few settlements -

there can be a “shift” to on e.g. on Anglesey, on Sark, on the

Isle of Wight. Not every English speaker makes that shift, but at this point

Latin would step in with the locative case.

Crēta: Crete > Loc. Crētae [locative]: on Crete

A large island such as Sicily with several settlements would

be “in Siciliā” [ablative]:

Gāius ¦ [i] Syrācūsīs ¦ [ii] in Siciliā ¦

habitat. Gaius lives ¦ [i] in Syracuse ¦ [ii] in Sicily.

[i] Syrācūsae [pl.]: Syracuse > Locative. Syracūsīs:

in Syracuse; that’s a place name and it takes a locative, full stop.

[ii] in Siciliā: not considered a small island and

so in + ablative is used just like you would say “in” with any

other noun

In Cicero and Plautus, however, we find:

“Rhodī [locative] enim” inquit “ego nōn fuī” (Cicero) ¦

“For I,” he says “Was not on Rhodes”

Samia mihi māter fuit: ea habitābat Rhodī [locative].

(Plautus) ¦ Samia was my mother: she lived on Rhodes.

Rhodos: Rhodes > Loc. Rhodī: on Rhodes i.e. considered to

be a small island and adheres to the rule.

Caesar paucōs diēs in Asiā morātus cum audīsset Pompēium Cyprī [locative]

vīsum (Caesar) ¦ When Caesar, having stayed for a few days in Asia had heard

that Pompeius had been seen in Cyprus.

Cyprus > Loc. Cyprī: in / on Cyprus i.e. considered (by

Caesar) to be a small island.

However, did the perception of individuals vary, just like

our own perceptions vary? Are all the writers consistent in what forms they

use? Look at the next quotation where both are used in the same sentence, and

note how Caesar wrote Cyprī but Varro writes in Cyprō.

Itaque Crētae [locative] ad Cortȳniam dīcitur platanus

esse, quae folia hieme nōn āmittat, itemque in Cyprō ... [in +

ablative] (Varro)

Thus near Cortynia, on Crete, there is said to

be a plane tree which does not shed its leaves in winter, and another in

Cyprus ...