This video shows some of the absolute basics of the language that were covered a long time back in the group; as always, you can scroll back or go to the other site. The video itself also has explanations at the end.

In a dialogue that

lasts just under two minutes, there is a lot of very useful information and so,

I’ll summarise the key points to take from it in two posts:

[1] Nouns of the 1st

and 2nd declension

ancilla, -ae [1/f]:

maidservant

domina, -ae [1/f]:

mistress

familia, -ae [1/f]:

family

fīlia, -ae [1/f]:

daughter

__________

dominus, -ī [2/m]

master

fīlius, -ī [2/m]: son

numerus, -ī [2/m]:

number

servus, -ī [2/m]: slave

līberī, -ōrum

[2/m/pl]: children

[2] Verb

sum, esse: be

[3] 1st / 2nd

declension adjectives and possessive adjectives:

cēterus, -a, -um: the

rest

magnus, -a, -um:

large; great

parvus, -a, -um: small

multus, -a, -um: much

(pl. many)

paucus, -a, -um: few

meus, mea, meum: my

tuus, tua, tuum: your

[4] Case usage

[i] Nominative

Dominus meus est

Iūlius. │ Julius is my master.

Aaemīlia domina mea

est. │Aemilia is my mistress.

Vīgintī nōn est parvus

numerus. │ Twenty isn’t a small number.

And the two speakers

deliberately express them in different ways to show the flexibility of the word

order.

singular > plural

servus

> multī servī │ many slaves

> cēterī servī │the other slaves

> quot servī? │how many slaves?

ūnus fīlius > duo fīliī: two sons

paucī līberī: few children

ancilla > decem ancillae: ten maidservants

Quot servī et quot ancillae* …? │ How many slaves and how many

maidservants …?

decem servī decemque ancillae* │ten slaves and ten maidservants

*They make a small

pronunciation error here:

Latin, like English,

has stressed syllables e.g. háppy, ínteresting, impórtant, begín; the last one – be-GIN has a stress

on the final syllable. In Latin, however, a word is not stressed on the final

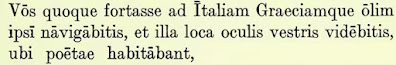

syllable e.g.

valē /ˈu̯a.leː/

servus /ˈser.u̯us/

ancillae /anˈkil.lae̯/

quoque /ˈkʷo.kʷe/

duo /ˈdu.o/

[ii] Genitive

Iūlius > familia ¦

Iūliī [literally: the family ¦ of Julius]: Julius’ family

dominus meus >

familia ¦ dominī meī [literally: the family ¦ of my master]: my master’s family

līberī > numerus ¦

līberōrum │ the number ¦ of children

servus > numerus ¦

servōrum │ the number ¦ of slaves

[iii] Ablative

familia tua > Quot

servī sunt ¦ in familiā tuā? │ How many slaves are ¦ in your family?

And here are both

cases working together in two of the questions.

Quot sunt līberī ¦ in familiā ¦ Cornēliī? │ How many children are ¦ in the family ¦ of Cornelius?

Quot servī et quot

ancillae sunt ¦ in familiā ¦ dominī tuī? │ How many slaves and how many

maidservants are ¦ in the family ¦ of your master?

[iii] Vocative: his

name is Titus but when Iosephus addresses him directly -us > -e

Valē, Tite │ Goodbye, Titus.