You’ve heard the words of Cicero; now hear the words of Donald Duck if Plautus had written it!

Monday, May 6, 2024

06.05.24: Cicero in action

This image shows a 19th century fantasised depiction by Maccari of Cicero denouncing Catiline in the Senate upon the discovery of his conspiracy to overthrow the authorities in Rome, which, ultimately, led to his death and the execution (without trial) of co-conspirators.

Cicero was a master orator and you can see the use he makes

of iste while lambasting Catiline in both its functions as [i] referring

to something to close to Catiline and [ii] the disdain in which Cicero hold

him.

Quotiēns iam tibi extorta est ista sıca dē manibus? │

How often already has that dagger been wrested away from your hands,

[i.e. it isn’t that Catiline is holding a dagger in his hand at that precise

moment, but Cicero associates a dagger i.e. the threat of murder with

Catiline]

Nunc vērō quae tua est ista vīta? │ But now what is

that life of yours?

And the one that the image itself depicts …

Quid? Quod adventū tuō ista subsellia vacuēfacta sunt … partem istam subselliōrum nūdam atque inānem relıq̄uērunt, │ What of the fact that at your arrival those seats around you were vacated, … they abandoned that part of the seats bare and empty..?

04.05.24: review; birthday plans [9] notes: other points (iv); demonstratives and pronouns [3]

iste, ista, istud

This is a classic example of why you can spend a lot of time pondering about some aspect of Latin grammar, until it finally dawns on you that you don’t really need to.

From Wiktionary, and we’ll go from there:

Iste, ista, istud “… is used to refer to a person or thing,

or persons or things, near the listener. It contrasts with hic

(“this”), which refers to people or things near the speaker, and ille (“that”),

which refers to people or things far from both speaker and listener.”

In the previous post we looked at hic and ille

[1]

How much is this book? [The book is right in front of you or

maybe it’s in your hand.]

This is a big problem. [It’s as if the problem is before

your eyes.]

i.e. this and these are ‘close’ to you

Latin: hic, haec, hoc

hic liber: this book

[2]

How much is that book? [The book is maybe on a shelf in the

store and you’re pointing to it].

I love that part of the city. [You’re refering to something

that exists but not physically there when you speak.]

i.e. that and those are away from you and from the person

you’re talking to.

Look at that mountain. [Neither the speaker nor the person

being addressed are near it.]

Latin: ille, illa, illud

ille liber: that book

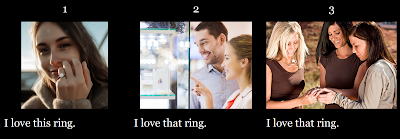

image #1: people talking about a ring

[1] and [2] are straightforward

[1] I love this ring (it’s on my finger and I’m showing it

to you): hic, haec, hoc

Hunc ānulum amō.

[2] I love that ring (that’s in the window away from both of

us): ille, illa, illud

Illum ānulum amō.

[3] It’s the third part of the image that we need to take a

look at. She likes the ring that’s on her friend’s finger i.e. what she is

referring to is close to the person she’s addressing. She isn’t pointing to

something that is distant from both of them.

English has no set rules for this but, sometimes, we like to

be specific in referring to something that is close to the

person you’re talking to.

That necklace looks really good on you. [He’s not referring to a necklace that’s in a shop window]

Let me take a look at that email you’re printing. [She’s not referring to an email that’s close to the person being spoken to]

[i] [image #2] Latin: iste, ista, istud: ‘that (person/thing)’; istī, istae, ista: ‘those (people/things)’

It has the same English translation as ille in the previous post, but it refers to a noun near the listener or connected to the listener. It is, therefore, sometimes known as the demonstrative of the second person because it refers to a noun near the person being directly addressed.

I love this restaurant. And do you see that waiter over

there? He’s from France. By the way, I love that watch. Did you get it for your

birthday?

That pupil of yours is always polite. [I’m

not talking about any pupil, but one who is associated with you i.e.

I am thinking about your pupil]

dē istīs rēbus exspectō tuās litterās

(Cicero) │ I’m waiting for your letter about affairs where

you are (translations vary but the idea is conveyed)

[ii] However, an important point about iste which

makes it stand out from ille you can first see in a possible

translation of it:

“What are you going to do about that son of yours?”

“That car of yours is always breaking down.”

Iste can be used negatively in Classical Latin,

to show disdain for a person or situation. Ille does

not convey that.

istae minae (Livy) │ those threats

(of yours)

A quick translation of that phrase in context shows its

negativity:

“and will you threaten the commons? will you threaten the

tribune? What, if you had not already twice experienced how little those

threats availed against the united sense of the people?”

Just focus on iste, look at the English context

and you can see why it’s being used. Also, the translator sometimes conveys it.

quae est ista praetūra? (Cicero) │ What

sort of a partnership is that of yours? (You take away a man's

inheritance, …)

tamen istum condemnētis necesse est

(Cicero) │ …, still you must condemn him (for it is not

permitted to us with impunity to rob one man for the purpose of giving to

another.)

quid quod adventū tuō ista subsellia

vacuēfacta sunt │ What of this, that upon your arrival those benches around

you / where you’re sitting were emptied,

Quid istud est negōtī? (Plautus) │ What

matter is this?

Think about a similar idea may be expressed: “What’s

all this / that about?” To express a

negative tone, an English speaker would stress the word. “Who does he

think he is?”

Here’s one from Plautus. English context …

“…he, together with his own son, is carousing with one

mistress the livelong day, and that he's secretly pilfering from her.”

ego istud cūrābō. │ I’ll take care of that.

Again, an English speaker would stress it with the implication there is some

problem.

Three points to take away from all of this:

[1] Whether you see forms of ille or iste,

both of them can be translated the same way

ille vir / iste vir: that man

illa femina / ista femina: that woman

Context would determine whether, in translation, the

negativity of iste / ista should be conveyed:

iste vir: that (wretched) man

ista fēmina: that (dreadful)

woman

illam amo: I love her

but …

istum odi: I hate him; I hate that

guy

[2] By Mediaeval times, there was no distinction in the use

of ille and iste, and iste had

lost its pejorative sense.

Two lines from the same song, and both mean the same:

bibit ille bibit illa │ he is

drinking, she is drinking

bibit ista bibit ille │she is

drinking, he is drinking

[Image #3] from another song in the same period:

Istud vinum, bonum vinum │ this wine,

good wine

[3] The other interesting aspect of ille and iste is

the way in which they “settled” into specific roles within the Romance

languages derived from Latin. Below are some examples.

La: ille > French le [i] the [masc.

sg.], and [ii] him

La: ille > French il: he

La: illa > French elle: she

La: illa > French la [i] the [fem. sg.],

and [ii] her

La: illōs / illās > French les [i] the

[pl.], and [ii] them

La: ille > Spanish [i] el: the, and [ii]

él: he

La: illa > Spanish [i] la: the, and [ii]

ella: she

La: illōs > Spanish los: the [masc. pl.]

La: illās > Spanish las: the [fem. pl.]

La: iste > Spanish este: this [masc. sg.]

La: ista > Spanish esta: this [fem. sg.]

La: istud > Spanish esto: this [neut. sg.]

You can see that some of them retained original Latin

meanings, but in both languages, and in other Romance languages, you see how

some of the original Latin words became definite articles i.e.

‘the’. In Classical Latin, however, there was no definite article; ille was

not used to express "the".

04.05.24: review; birthday plans [8] notes: other points (iv); demonstrative adjectives and pronouns [2] Examples of ille from the authors

If we ever had the opportunity to travel back in time, which Roman authors would we like to have met? For me, one of them would have been Plautus.

I can’t talk about the

tradition of comedy in any other nation, but certainly British comedy often

plays on the respective roles of men and women; men think they’re

in charge, but it’s the women who call the shots. The men think they’re

brave, but when the wives turn up, it’s a different story!

And that story has been

going on for more than 2000 years.

From Plautus: Asinaria (the

Comedy of Asses); date uncertain: possibly 200BC

ARGYRIPPUS: Ecquid mātrem

amās? │ Don't you love my mother?

DEMAENETUS: Egone illam?

nunc amō, quia nōn adest. │ Who, me? I love her just now,

because she isn't here.

I also like his work

because, of course, they’re plays, they’re talking to a Roman

audience, and so the language can be simpler and can illustrate points in

context. He’s a very handy author for Facebook!

[1] Here are a few examples

from Plautus of ille, illa and illud being

used in context.

ARTEMONA: Ille it

ad cēnam cottīdiē. │ He's going out to dinner every

day.

PARASITUS: Quīn tū illum iubēs

ancillās rapere sublīmen domum? │ Why don't you tell your maid-servants to

carry him off home upon their shoulders?

ARTEMONA: Tacē modo. nē ego

illum ēcastor miserum habēbō. │ You just keep quiet. Oh, I'll

surely make him miserable.”

PARASITUS: Ita fore illī dum

quidem cum illō nūpta eris. │ I'm sure that’s

what’ll happen to him, so long, indeed, as you stay married to

(with) him.”

One character is suggesting

a sort of ‘pre-nuptial’ agreement.

tū prō illā ōrēs

ut sit propitius. neque illa ūllī hominī nūtet, nictet, annuat. │

You are to pray for her (on her behalf) that he (the god) be

favourable, and she is neither to nod at any man, wink, or

make a sign.

nam ego illud argentum

tam parātum fīliō sciō esse │ For I know that money is as

surely forthcoming for my son

[2] Catullus 51:

Ille mī pār esse deō vidētur, │He / that

(man) seems to me to be equal to a god

ille, sī fās est, superāre

dīvōs, │He, if it’s permissable, (seems to) surpass the gods

And it’s a spot-on example

because Catullus is jealously looking at him from a distance, and that

man is with the girl that Catullus loves.

04.05.24: review; birthday plans [7] notes: other points (iii); demonstrative adjectives and pronouns [1]

Vincent makes three statements in the video that refer to important points of grammar:

1. Sed nōn possum hoc vītāre.

│ But I cannot avoid this.

2. Quod illam terram

valdē amō. │Because I really love that region.

3. Is fīet

sacerdōs. │ He will become a priest.

In this post we’ll look at

the first two.

Different grammar books or

online references are not always consistent in how they interpret or label

them.

Demonstrative adjectives

The term demonstrative itself

comes from Latin:

dēmōnstrō, dēmōnstrāre [1]:

show; point out; draw attention to

I like this book but I don’t

like that book.

‘This and that’ are

demonstrative adjectives i.e. they are used to describe,

to ‘point to’ an object or person that is near to you (this / these):

- How much is this book?

- These people are talking too loudly. They’re getting on my nerves.

‘That / those’ refer to

something or someone further away and often to someone or something that isn’t

physically there e.g.

- Can you show me that shirt on the shelf?

- How much are those cakes?

- I was in the bank. I really don’t like that manager.

- Have you tried those cakes which they sell in the supermarket?

Latin, like English, has

different words to express these ideas:

[1] hic [masc.], haec

[fem.], hoc [neut.]: this [pl. these]

- hic liber: this book

- hī mīlitēs: these soldiers

[2] ille [masc.], illa

[fem.], illud [neut.]: that [pl. those]

From the video:

- Quod illam terram valdē amō. │Because I really love that region.

He isn’t there; he’s

referring to something that is away from him and that he cannot even see.

If he said …

Hanc terram valdē amō. │ I really

love this region.

…he’s in it.

Both [1] and [2], however,

can also stand alone as demomnstrative pronouns i.e. they can

mean he / she / it [pl. they]

[1] hic, haec, hoc:

this (man), this (woman), this (thing); he / she / it [pl. these men / women /

things; they]

From the video:

- Sed nōn possum hoc vītāre. │ But I cannot avoid this / it.

It’s as if the situation

he’s referring to is right in front of him.

[2] ille, illa,

illud: that (man), that (woman), that (thing); he / she / it [pl. those men

/ women / things; they]

Here are some simple

sentences; the declension of hic and ille is

uploaded to files:

[A]

1. Hunc virum

timeō. │I fear this man.

2. Cūr ad hanc īnsulam

nāvigāmus? │ Why are we sailing to this island?

3. Quis hoc templum

aedificat? │ Who’s building this temple?

4. Ancillae hōs librōs

portant. │ The maidservants are carrying these books.

5. Servī hās amphorās

portant. │ The slaves are carrying these amphorae.

6. Barbarī ad haec castra

properant. │The barbarians are rushing to this camp.

7. Post hoc aedificium

est via lāta. │ There’s a wide steet behind this building.

8. Amīcus meus in hāc viā

habitat. │ My friend lives in this street.

9. Quis haec arma

timet? │ Who is afraid of theseweapons?

10. Hic dīxit:

Possum dēstruere templum Deī, et post trīduum reaedificāre illud. (Vulgate)

│ He said: “I can tear down the temple of God, and after three

days rebuild it.

11. Vulpēs hunc vīdit

(Phaedrus) │ The fox saw him.

12. Hanc amāvit

Iuppiter. (Servius) │ Juppiter loved her (this

girl).

[B]

1. Puella illum puerum

nōn amat. │ The girl doesn’t love that boy.

2. Vidēsne illōs puerōs

in fluviō? │ Do you see those boys in the river?

3. Cūr ad illam īnsulam

nāvigant? │ Why are they sailing to that island?

4. Vidēsne illās stēllās

in caelō? │ Do you see those stars in the sky?

5. Agricolae agrōs in illīs locīs

possident. │ The farmers own the fields in those places.

6. Illa puella

in illā tabernā labōrat. │ That girl works

in that shop.

7. Illae fēminae

in Ītaliā nōn nātae sunt. │ Those women were not

born in Italy.

8. Quis in illō oppidō

habitat? │ Who lives in that town?

9. Illud vīnum

valdē amō. │ I love that wine very much.

10. Estne ille amīcus

tuus? │ Is he your friend?

11. Illī ex

Hispāniā oriundī sunt. │ They are from Spain.

12. Illam amō. │

I love her (that girl).

Image #1: hic being

shown both as demonstrative adjectives and pronouns

Image #2: ille being

shown both as demonstrative adjectives and pronouns

The video links go into a

lot of detail on this; as I’ve said before, don’t try to amass all the

information at once (I didn’t); just focus on the existence of the two,

recognise them when you’re reading, and pick up the endings as you go along.

[1] hic, haec, hoc

[2] ille, illa, illud

03.05.24: the two steps of translation

A member made a great comment on a quotation that was being discussed:

errāre hūmānum est, persevērāre autem

diabolicum

It was used to show that, in

Latin and in English, the infinitives match ie.

to make mistakes is human, but to

persist in them is diabolical

I then talked about the

"two stages of translation"

[i] to make mistakes

is human, but to persist in them is diabolical.

That is stage #1: the literal translation

to recognise the grammatical structures and to see that those structures match.

A member then, quite

rightly, wrote:

"Put in idiomatic English: making mistakes

is human; persisting in them ... is diabolical."

The member gives stage [ii]

i.e. the one that sounds more natural in English, and he couldn't have picked a

better one i.e. errāre and persevērāre are infinitives - and, at the learning

stage, they need to be recognised as such - only then, once you go past stage

[i], you then put them it into stage [ii].

As I mentioned, you can't

by-pass stage #1 otherwise you might think that those infinitives errāre and

persevērāre have some in-built -ing meaning, but they

don't although they are often used to convey that idea.

And it will come up again

and again the more Latin you're dealing with and how it is best translated.

03.05.24: review; birthday plans [6] notes: other points (ii); numbers

Mox erō duodētrīgintā annōs nātus. │ I will soon be 28 years old.

Est [diēs] duodētrīcēsimus mēnsis

Maiī. │ It’s the 28th (day) of May.

Numbers have been covered in

detail in many previous posts and so I’m just going to say a little about them

and give some links.

There are three key areas.

Latin has different types of

numbers, but the two which, by far, matter the most are:

[1] cardinal numbers

(1, 2, 3 etc.) and [2] ordinal numbers (1st, 2nd, 3rd etc.)

Links to main posts on

numbers in the group:

26.02.24: cardinal numbers 1

– 10

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/04/26_4.html

28.02.24: cardinal numbers

11-20

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/04/lying-about-your-age-numbers-11-20-step.html

19.03.24: cardinal numbers

20-100

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/04/190324-more-on-numbers-20-100-how-to.html

21.03.24: ordinal numbers

1st – 10th

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/04/220324-video-ordinal-numbers.html

22.03.24: ordinal numbers

1st – 10th

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/04/220324-ordinal-numbers-2-telling-time.html

09.04.24: ordinal numbers

11th – 31st

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/05/090424-more-on-ordinal-numbers-11th-31st.html

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/05/090424-practice-with-ordinal-numbers.html

https://adckl.blogspot.com/2024/05/090424-practice-with-ordinal-numbers-2.html

[2] Image #1: in terms of

reading Latin, you also need to know the Roman numerical symbols and the way in

which those numerical symbols are put together:

I, V, X, L, C, D, M

When you’re reading in Latin

sometimes the editor will use full Latin numbers and sometimes Roman numerals.

[3] Further links:

1. Latin tutorial; Numbers

in Latin

2. Latin tutorial; Roman

Numerals

3.

https://dcc.dickinson.edu/.../cardinal-and-ordinal-numbers

4.

https://en.wiktionary.org/.../Appendix:Latin_cardinal...

[4] Like English or other

languages, you can be dealing with [i] a single number or [ii] a compound

number i.e. comprising two or more other numbers

quīnque: five

ūndecim: eleven

vīgintī ūnus: twenty-one

With the compound numbers,

variations can occur. Dickinson (link given) shows an example of that:

21: vīgintī ūnus; ūnus (et)

vīgintī i.e. the same as English twenty-one or German ein¦und¦zwanzig

[5] Image #2: note the

unusual feature of 18 and 19

18: duodēvīgintī;

duo¦dē¦vīgintī i.e. two from twenty

19: ūndēvīgintī;

ūn¦dē¦vīgintī i.e. one from twenty

And that applies to all the

compounds ending in 8 or 9; this is what Vincent uses in the video:

- Mox erō duodētrīgintā annōs nātus. │ I will soon be 28 years old.

duo¦dē¦trīgintā i.e. two

from thirty

- Est [diēs] duodētrīcēsimus mēnsis Maiī. │ It’s the 28th (day) of (the month of) May.

duo¦dē¦trīcēsimus i.e. two

from the thirtieth

[6] Image #3: all the

cardinal numbers from 1- 1000

03.05.24: review; birthday plans [5] notes: other points (i)

[1] soleō, solēre [2]: be in the habit of / accustomed to [doing something]

I mentioned in a previous

post about the “two steps” to translation

[i] start with the literal:

- Soleō facere pelliculās ... │ I am accustomed to make [= to making films] …; I am in the habit of making films …

There is nothing

grammatically wrong with the sentence and it is a common way in Latin of

expressing the concept. It is perfectly acceptable English, but it sounds

clumsy and old-fashioned.

[ii] Then think about how

you would most neatly render it in your own language:

I usually make

films …

And the reason I mention

this is:

Imagine you saw that

translation only at “stage 2”

- Soleō facere pelliculās ... │ I usually make films …

If you’re brand new to

Latin, you might think: “OK, soleo means ‘usually’

or, facere means ‘I make’; but they don’t. That’s why it’s

crucial to go through the first stage of literal translation.

[2] use of infinitives

The Latin infinitive has

multiple uses, some of which involve considerable study. However, there are

examples where English and Latin match.

[i] debeō, debēre [2]: owe;

must / ought / should

- Quid dēbeō ¦ facere ¦ igitur? │ What, therefore, ought I ¦ to do? What, therefore, do I have ¦ to do?

[ii] possum, posse [irr.]:

be able

- Sed nōn possum hoc ¦ vītāre. │ But I cannot avoid this. I am not able ¦ to avoid ¦ this.

[iii] oportet: it is

necessary / proper

Again, a similar example of

the “two step” translation:

Oportet by itself does not

refer to anybody in particular

- oportet ¦ cūrāre ¦ et mentem et corpus │ it is necessary ¦ to take care of ¦ (one’s) mind and body = You need to take care of … (but not addressing anybody in particular i.e. like the French pronouns on or man)

It can, however, be used

with pronouns to refer to a specific person:

- oportet nōs patriam ¦ amāre │Literally: it is appropriate / proper for us ¦ to love ¦ the country = We ought ¦ to love ¦ or we should love the country.

Caesarī ¦ tē oportet

¦ adsistere (Vulgate) │ You must ¦ stand ¦

before Caesar!

[iv] facile est: it’s easy

- nōn est facile ¦ exercēre ¦ mentem │ It isn’t easy ¦ to train ¦ the mind.

[v] coepī: I began

- coepī ¦ currere │ I started / began ¦ to run; I started running.

[image] the famous quotation

showing a match between English and Latin in the use of the infintive:

- Errāre hūmānum est, persevērāre autem diabolicum. │To err is human, but to persist [in error] is diabolical.

03.05.24: review; birthday plans [4] notes: passive

There are two sentences in the video which refers to an aspect of Latin grammar that’s very important and occurs a lot in the literature.

Et vidētur frāter

meus illīc. │ And my brother is seen over there.

Mox ōrdinābitur.

│ Soon he will be ordained.

[Image #1]: I deliberately

created that word cloud because I sometimes like to share my own experiences of

learning Latin.

Maybe the word cloud looks

“nice”, but it can also look frightening.

And I chose it for this

feature of Latin because, when I first saw all of these – and many, many more –

all on the same page, my reaction was “that’s too high a hill to climb.”

Unfortunately, most

textbooks – especially the older ones - will give you a long list of all the

passive verbs in every form with a subliminal “good luck with that” message.

And then I got a hold of

“Teach Yourself Beginners Latin” by Sharpley, and Sharpley explained a major

part of it in one sentence.

So here’s how I went about

it.

Step #1: What is

the passive? Get the explanation first. With respect, some

people like to refer to grammatical terms because they know

them, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that anybody else does. If there is

ever a grammatical term referred to in the group, and you're not sure what it

means, then simply ask.

[1] The soldier killed the

king.

We call this the active voice;

it was the soldier who did the killing. Whenever we say “I often buy cakes”,

“You were not telling me the truth”, “John will organise that”, that is the

active voice because ‘I’ and ‘you’ and ‘John’ are performing the actions.

[2] The king was

killed by the soldier.

This is the passive voice;

the king did not do anything but, rather, something happened to him.

“Cakes are sold in

that shop”, “The man was being threatened by the burglar”,

“The email will be sent later today”; the cakes, the man and

the email aren’t doing anything, but something is being done to them.

Stage #2: build on what you

already know

If you can’t run 100 metres,

you can’t run 200.

The four conjugations of the

verbs in the three tenses covered so far in the group need to be known first.

If you have to look at some or all of that, then use the information in the

group or in the files, or any other resources you have. And, as always, use the

group to ask questions.

Stage #3: You don’t have to

do everything at once.

The Sharpley book only

focused on one part the passive i.e. when you are talking about another person

/ thing (3rd person singular in grammar) or other people / things (3rd person

plural in grammar) in the three tenses already discussed in the group. He made

no reference to any other part of the passive. Sure, there are other aspects of

this further down the road, but, for me, a step-by-step approach worked.

Present active

portat: he / she / it

carries

portant: they carry

Present passive

[Image #2]: the Sharpley

sentence; all you do is add -ur

portātur: he / she

/ it is (being) carried

portantur:

they are (being) carried

From the video:

Et vidētur frāter meus illīc

│ And my brother is seen over there.

videt: he / she / it sees

> vidētur: he / she /

it is seen

And we can rework it into a

more common English way of saying it:

Et vidētur frāter meus

illīc. │ And you can see my brother over there.

And that’s the same for the

other tenses covered so far:

Imperfect

portābat: he / she / was

carrying

portābant: they were

carrying

> portābātur: he /

she / it was (being) carried

> portābantur:

they were (being) carried

future

portābit: he / she / it will

carry

portābunt: they will carry

> portābitur: he /

she / it will be carried

> portābuntur:

they will be carried

From the video:

ōrdinābit: he / she will

ordain; appoint to office

> ōrdinābitur: he / she

will be ordained

Of course, Sharpley then

goes on to look at other parts of this, but the point is that he recognises

that we don’t acquire language in enormous truckloads all at the same time, any

more than we did when we were learning our own language as children.

[Image #3]: I still have the

book!