Saturday, May 11, 2024

12.05.24: review; future tense [5]; the future tense of 3rd, 3-iō and 4th conjugation verbs

Match the English verbs with the verbs in the word cloud (it isn’t colour coded)

1. he will feel

2. I shall do

3. they will feel

4. they will say

5. he will sleep

6. you (sg.) will run

7. we will sleep

8. you (pl.) will do

9. I shall say

10. you (pl.) will take

11. we will run

12. you (sg.) will take

12.05.24: review; future tense [4]; the future tense of 3rd, 3-iō and 4th conjugation verbs

The future tense of 1st and 2nd conjugation verbs are easy to spot because they have distinctive markers i.e. -bō / -bi- / -bu-

Images #1 – 3 show you the

endings for the 3rd, 3-iō and 4th conjugation

mittō, mitt│ere [3]: send

remove -ere

> mitt-

> add the endings:

mittam: I shall send

mittēs: you (sg.)

will send

mittet: he / she / it

will send

mittēmus: we will

send

mittētis: you (pl.)

will send

mittent: they will

send

[ii] In the 4th conjugation

-re is removed from the infinitive, but the long /ī/ is shortened > /ĭ/:

audī│re: hear

> audī- > audĭ¦-

Then add the same endings:

audiam, audiēs,

audiet, audiēmus, audiētis, audient

[iii] 3rd-iō verbs endings

are exactly the same as the 4th conjugation:

capiō, capere [3-iō]: take

Remove the infinitive ending

in its entirety:

cap¦- > add short /ĭ/:

capi-

Then add the endings:

capiam, capiēs,

capiet, capiēmus, capiētis, capient

Match the Latin and English

verbs:

1. legam

2. fugiēs

3. audiet

4. legēmus

5. scrībētis

6. venient

7. fugiam

8. mittēs

9. audient

10. veniēmus

11. iaciētis

12. iacient

I shall flee; I shall read;

she will hear; they will come; they will hear; they will throw; we will come;

we will read; you (pl.) will throw; you (sg.) will flee; you (sg.) will write;

you (pl.) will write

11.05.24: Iōsēphus et Titus servī sunt; notes on the video [2]

[5] conjunctions i.e. words that join two parts of a

sentence

[i] sed: but

[ii] neque: and .. not …

Neque tua est familia!│And it’s not (even)

your family!

[iii] Two ways of saying ‘and’:

[a] et: and

[b] -que which is added to the end of the word

Centum servī ancillaeque │ a hundred

slaves and maidservants

Decem servī decemque ancillae │ ten slaves and ten

maidservants

[6] Asking questions

[i] -ne: can be attached to the first word of a sentence to

form a question

Estne magna familia Iuliī? │ Is Julius’ family

large?

[ii] question words (in grammar known as interrogatives)

quis?: Who?

quot?: How many?

[iii] Num cēterī servī Cornēliī tuī servī

sunt?

In the subtitles, they translate it as: “So, are the rest of

Cornelius’ slaves your slaves as well?” That’s a very neat translation but we

need to take it apart a bit:

Two words: [a] nōnne and [b] num;

both can be used to ask a question and, in English, the best way to remember

these two is with 2 possible translations of each

[a] nōnne expects a ‘yes’ answer

Nōnne intellegis? │ [i] Surely you

understand? [ii] You understand, don’t you?

[b] num expects a ‘no’ answer

Num Gallia īnsula est? │ [i] Surely Gaul

isn’t an island? [ii] Gaul isn’t an island, is it?

So, by rephrasing the subtitle, you can see how that

word num is working:

Num cēterī servī Cornēliī tuī servī sunt?

[i] Surely the rest of Cornelius’ slaves aren’t your slaves?

[ii] The rest of Cornelius’ slaves aren’t your slaves, are

they?

Of course, they’re not his slaves i.e. he expects a ‘no’

answer.

11.05.24: Iōsēphus et Titus servī sunt; notes on the video [1]

This video shows some of the absolute basics of the language that were covered a long time back in the group; as always, you can scroll back or go to the other site. The video itself also has explanations at the end.

In a dialogue that

lasts just under two minutes, there is a lot of very useful information and so,

I’ll summarise the key points to take from it in two posts:

[1] Nouns of the 1st

and 2nd declension

ancilla, -ae [1/f]:

maidservant

domina, -ae [1/f]:

mistress

familia, -ae [1/f]:

family

fīlia, -ae [1/f]:

daughter

__________

dominus, -ī [2/m]

master

fīlius, -ī [2/m]: son

numerus, -ī [2/m]:

number

servus, -ī [2/m]: slave

līberī, -ōrum

[2/m/pl]: children

[2] Verb

sum, esse: be

[3] 1st / 2nd

declension adjectives and possessive adjectives:

cēterus, -a, -um: the

rest

magnus, -a, -um:

large; great

parvus, -a, -um: small

multus, -a, -um: much

(pl. many)

paucus, -a, -um: few

meus, mea, meum: my

tuus, tua, tuum: your

[4] Case usage

[i] Nominative

Dominus meus est

Iūlius. │ Julius is my master.

Aaemīlia domina mea

est. │Aemilia is my mistress.

Vīgintī nōn est parvus

numerus. │ Twenty isn’t a small number.

And the two speakers

deliberately express them in different ways to show the flexibility of the word

order.

singular > plural

servus

> multī servī │ many slaves

> cēterī servī │the other slaves

> quot servī? │how many slaves?

ūnus fīlius > duo fīliī: two sons

paucī līberī: few children

ancilla > decem ancillae: ten maidservants

Quot servī et quot ancillae* …? │ How many slaves and how many

maidservants …?

decem servī decemque ancillae* │ten slaves and ten maidservants

*They make a small

pronunciation error here:

Latin, like English,

has stressed syllables e.g. háppy, ínteresting, impórtant, begín; the last one – be-GIN has a stress

on the final syllable. In Latin, however, a word is not stressed on the final

syllable e.g.

valē /ˈu̯a.leː/

servus /ˈser.u̯us/

ancillae /anˈkil.lae̯/

quoque /ˈkʷo.kʷe/

duo /ˈdu.o/

[ii] Genitive

Iūlius > familia ¦

Iūliī [literally: the family ¦ of Julius]: Julius’ family

dominus meus >

familia ¦ dominī meī [literally: the family ¦ of my master]: my master’s family

līberī > numerus ¦

līberōrum │ the number ¦ of children

servus > numerus ¦

servōrum │ the number ¦ of slaves

[iii] Ablative

familia tua > Quot

servī sunt ¦ in familiā tuā? │ How many slaves are ¦ in your family?

And here are both

cases working together in two of the questions.

Quot sunt līberī ¦ in familiā ¦ Cornēliī? │ How many children are ¦ in the family ¦ of Cornelius?

Quot servī et quot

ancillae sunt ¦ in familiā ¦ dominī tuī? │ How many slaves and how many

maidservants are ¦ in the family ¦ of your master?

[iii] Vocative: his

name is Titus but when Iosephus addresses him directly -us > -e

Valē, Tite │ Goodbye, Titus.

Friday, May 10, 2024

11.05.24: Latin tutorial; future tense of 3rd, 3-iō and 4th conjugation verbs

Before moving on to the second type of future tense, you might want to take a look at this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FTBG0Jg6Cg

As examples he uses

the verbs trahō, trahere [3]: drag; pull, and audiō, audīre [4]: hear

11.05.24: review; future tense [3]; working with different tenses; the sī clause [3]: Julia: a Latin Reader [3]

Identify the present tense verbs and the future tense verbs

from this passage.

1. they will fight

2. they will have

3. they will kill

4. we have

5. we live

6. we love

7. we will be

8. And the imperative / command form: Farewell! Be well!

____________________

“in casīs Rōmānīs laetae et placidae habitāmus; līberōs

cārōs habēmus et vehementer amāmus; et Sabīnōs et Rōmānōs amāmus. "Sī

Rōmānī cum Sabīnīs pugnābunt, Rōmānī Sabīnōs, Sabīnī Rōmānōs necābunt. Tum

Sabīnae nec virōs nec patrēs nec frātrēs habēbunt. Ō patrēs, valēte! Nōn iam

Sabīnae sed Rōmānae semper erimus fīliae vestrae."

____________________

Vocabulary and notes

nec … nec: neither … nor …

nōn iam: no longer

As you go on reading Latin, features will “turn up” that,

from my own experience, if you try to deal with all of it at once, it’s too

much information at one time and, to be honest, of little help if you’re not

seeing it in context.

This little text is a case in point:

"Sī Rōmānī cum Sabīnīs pugnābunt,

Rōmānī Sabīnōs, Sabīnī Rōmānōs necābunt. │ If the

Romans fight with the Sabines, the Romans will kill the Sabines and the Sabines

(will kill) the Romans.

Sī (if) introduces what in grammar is known as

a conditional clause.

If I have time, │I will go to the bank.

If I have time, both in English and in Latin, is

called a conditional clause. That part of the sentence e.g. an action or a set

of circumstances has to exist before │ the main action of the sentence can take

place.

If he doesn’t do his homework (conditional

clause) │I’ll be really angry (the outcome).

[i] The standard format for that construction in English is:

If it rains [present tense] tomorrow │we will not go

out [future tense].

But you also see this:

[ii] If he won’t tell [future] you the answer │then it’ll be

[future] your problem and not mine.

Now look at the Latin example; in this type of conditional

sentence, Latin uses the future tense in both parts of this sentence.

Sī Rōmānī cum Sabīnīs pugnābunt, │ Rōmānī

Sabīnōs, Sabīnī Rōmānōs necābunt.

If the Romans (will) fight with the Sabines

│ the Romans will kill the Sabines, (and) the Sabines will kill the Romans.

Step-by-step: that’s by no means the whole story.

Conditional sentences in Latin are a big topic that involve a lot of focus on

verbs and so simply be aware that tense usage between English and Latin does

not always match.

____________________

We live, happy and peaceful, in Roman houses; we have our dear children and love them very much; we love both the Sabines and the Romans. If the Romans fight with the Sabines, the Romans will kill the Sabines, (and) the Sabines will kill the Romans. Then the Sabines will have neither husbands, nor fathers, nor brothers. O fathers, farewell! No longer Sabines but Romans, we will always be your daughters.

10.05.24: follow-up on the previous post

The history of Ancient Rome is massive and complex. When I started, my knowledge of Roman history was vague. But certain stories came up – again and again – in the old school textbooks. In an earlier post, an excerpt referred to Aeneas’ escape from Troy. Two posts back reference was made to Romulus.

Long before I could

look at these stories in original Latin, I learned about early Roman history –

and the characters who figure in them – by using books such as Julia, a

Latin reader, because they tell the stories in simpler language.

In earlier posts I

have used many excerpts from:

[i] Helen

Chesnutt’s The Road to Latin; they give a lot of background to the

lives of the Romans

[ii] Sonnenschein’s Ora Maritima; the author talks a lot about the history of Roman Britain, and you can review basic Latin while you're doing it.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924031202850

Slowly, I identified

areas of Roman history that were of significance and, gradually, I began to

read more detailed works, first in English and then in Latin. What were the

major events – both historical and in legend? How do some of these narratives

forge the Romans’ mindset? What was their ‘value system’, and who were the

‘major players’ – good and bad?

I think that Reading

Latin by Jones and Sidwell [image #1] is a fabulous ‘step up’ into the

world of Roman history and literature in Latin. Jones and Sidwell, starting

from Plautus, choose parts of original texts – and they provide extensive notes

and vocabulary. An example in the book is the trial against Gaius Verres for

his gross mismanagement of Sicily. Cicero was the prosecutor. The entire trial

is monumental in length, but Jones and Sidwell pick out significant parts of it

in Latin, and give the historical background and some insight into how the

Romans viewed provincial management.

In the way that I

referred to Wiktionary as being the ‘middle man’ in terms of dictionaries, for

me Jones and Sidwell are the ‘middle men’ in accessing the literature and the

history in the original language.

Here is the link again

to Julia – a Latin reader, the entire basic book that I’m using at

the moment for these posts if you want to read more for yourself; there, among

others, you'll find Romulus and Remus, the Sabines, Mars, and the Trojan horse.

https://www.fabulaefaciles.com/library/books/reed/julia

Although not mentioned

by name in the first excerpt in the previous post, the incident being described

concerns Horatius on the bridge.

The second text refers

to an event in the legendary history of early Rome which is known by the ugly

term ‘The rape of the Sabine Women’ although it is sometimes translated as

‘abudction’ or ‘kidnapping’. Personally, I think that, in the context of that event,

‘rape’ is too provocative, whereas in relation to the rape of Lucretia –

another major story in the early history / legend of Rome - the word

means precisely that. The rape / abduction / kidnapping

(delete as applicable) of the Sabine women was a story known to all the Romans.

More information is at the link below:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rape_of_the_Sabine_Women

More than that, they

“commemorated” it on their coins [mages #2 and #3] And the coins too can be

part of the ‘jigsaw’ of getting to know the Romans.

In an earlier post

there was a discussion on the coin depicting Aeneas escaping from Troy, his

father on his shoulder and the household god in his right hand, symbolic of

Rome’s earliest history, bravery, duty to the gods and duty to the family.

Another post also

looked at the Ides of March coin commemorating the murder of Julius Caesar in,

for me, a blatant political manoeuvre, since it was minted on the order of

Brutus, one of the men who had stabbed Caesar to death.

But why would a coin

commemorating the abduction of women be minted? What was in the psyche of the

Romans that a coin like that would "celebrate" such an event -

whether true or legendary? I don’t know the “answer”, but I suspect that it

embedded the idea that the Romans could take whatever they wanted. And, judging

by the size of the Roman Empire at its height, they kept on doing it.

Thursday, May 9, 2024

10.05.24: review; future tense [2]; working with different tenses: Julia: a Latin Reader [2]

[1]

"Ego cum duōbus amīcīs contrā hostēs in angustō locō

pugnābō. Ita omnēs prō ārīs templīsque Rōmānīs, prō uxōribus līberīsque, prō

sacrīs virginibus pugnābimus. Ita urbem Rōmam cōnservābimus. Quis mēcum in

extrēmō ponte stābit et contrā Etrūscōs pugnābit?"

Tum Lartius, "Ego," inquit, "ā dextrā stābō,

et pontem tēcum cōnservābō"; et magnā vōce Herminius, "Ego,"

inquit, "ā sinistrā stābō et pontem tēcum cōnservābō."

[A] Vocabulary and notes

[i] 1st / 2nd declension adjectives in -er

sacer, sacra, sacrum: sacred; holy

dexter, dextra, dextrum: right

sinister, sinistra, sinistrum: left

[ii] prepositions with the accusative:

contrā: against; contrā Etrūscōs │against the

Etruscans

[iii] uses of the ablative case

prepositions

in angustō locō │in a narrow

position

in … ponte │on the bridge

cum … amīcīs │with…friends

mēcum: with me; tēcum: with you, i.e. written

as one word with the preposition attached to the pronoun

prō: [i] in front of; before [ii] for; on behalf of:

We will fight …

prō ārīs templīsque Rōmānīs… │for the

Roman altars and temples (or standing in front of / before the

altars and temples; either way, they intend to protect them)

prō uxōribus līberīsque │for (our) wives and

children

ā / ab: (away) from, but here:

ā dextrā │on the right

ā sinistrā │on the left

But we have the same idea in “The enemy attacked from the

right.”

Other uses of the ablative case have been discussed as the

group has gone on. Here is an example from the text.

magnā vōce │ (he said) in a

loud voice; the ablative expresses the way in which he said it

[B] Find the Latin from the text.

1. I shall fight

2. I shall preserve.

3. I shall stand.

4. Who will fight?

5. Who will stand?

6. We will fight.

7. We will preserve.

Much of what you read in Latin will be in different

tenses at the same time. Here are some “gentle” examples.

[2]

"Ō cīvēs," inquit, "nūllās fēminās habēmus,

sed Sabīnī cīvitātem fīnitimam habitant. Sabīnī fēminās multās et fōrmōsās

habent. Sabīnōs igitur cum fēminīs ad lūdōs invītābimus, et virginēs

raptābimus."

cīvitās, cīvitātis [3/f]: multiple meanings e.g. state; city

and surrounding territory; kingdom; tribe

fīnitimus, -a, -um: neighbouring

[3]

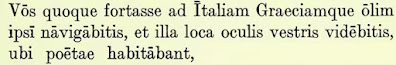

Vōs quoque fortasse ad Ītaliam Graeciamque ōlim ipsī

nāvigābitis, et illa loca oculīs vestrīs vidēbitis, ubi poētae habitābant.

From [2] and [3]:

Find the Latin

[i] Present tense

The Sabines … have many beautiful women

The Sabines … live

We have…

[ii] Imperfect

The poets used to live

[iii] Future

You [pl.] will sail

You [pl.] will see

We will abduct

We will invite

___________________

[1] I will fight with two friends against the enemies in a

narrow place. Thus we will all fight for the Roman altars and temples, for our

wives and children, for the sacred (Vestal) virgins. Thus we will preserve the

city of Rome. Who will stand with me at the end of the bridge and fight against

the Etruscans?"

Then Lartius said "I will stand on the right, and

maintain the bridge with you." and Herminius with a loud voice said

"I will stand on the left and guard the bridge with you.”

[2] "Oh citizens," he said, "we have no

women, but the Sabines live in a neighbouring state. The Sabines have many

beautiful women. Therefore we will invite the Sabines with the women to the

games, and we will abduct the young women."

[3] Perhaps you yourselves will also sail to Italy and

Greece one day, and will see with your own eyes those places where the poets

used to live.

09.05.24: review; future tense [1]: Julia: a Latin Reader [1]

The future tense translates as “I shall / will, you will” etc.

Latin forms its future tense

in two different ways depending on the conjugation to which a verb belongs.

This post and the next one

show the first form which is used with 1st and 2nd conjugation verbs.

Both the 1st and 2nd

conjugation verbs do the same: take the infinitive e.g. amāre [1]

and habēre [2], get rid of the infinitive ending -re and then add

the future tense endings.

1st conjugation

amā│re: love

> amā -

ama│bō: I

shall love

ama│bis: you

(sg.) will love

ama│bit: he /

she / it will love

ama│bimus: we

will love

ama│bitis: you

will love

ama│bunt: they

will love

2nd conjugation

habēre: have

> habē-

habē│bō: I

shall have

habē│bis: you

(sg.) will have

habē│bit: he /

she / it will have

habē│bimus: we

will have

habē│bitis:

you will have

habē│bunt:

they will have

Look at the parts in

italics: they are the ‘markers’ for the future tense of these conjugations.

-bō / -bi- / -bu-

Image #1: the endings of the

future tense for the first / second conjugation

Image #2: example of the

first conjugation verb amō, amāre [1]: love

Image #3: example of the

second conjugation verb moneō, monēre [2]: warn

image #4: the irregular

verb sum, esse: be; in all three tenses covered so

far

The two excerpts below, both

from Julia: a Latin Reader (Reed) show the future tense of the first and second

conjugation verbs in context. The originals are also posted as images.

[1] “Nunc in caelō et in

stēllīs cum patre tuō cēterīsque dīs rēgnābis. Fīlium meum ad

caelum portābō."

["Now you will

reign in heaven and in the stars with your father and other gods.

I will take my son to heaven."]

[2] Sed Rōmulus verbīs

benignīs, "Ō Iūlī," inquit, "nūlla est causa timōris. Nunc

Quirītēs nūmen meum adōrābunt et Rōmulum Quirīnum vocābunt.

Templa et ārās aedificābunt, et ad ārās dōna apportābunt.

Semper artem bellī et arma cūrābunt, et corpora in armīs dīligenter

exercēbunt. Ita Quirīnus Populum Rōmānum servābit."

[But Romulus, with kind

words, said, "O Julius," said, "There is no cause for fear. Now

the Quirites* will worship my divine will and will

call Romulus Quirinus**. They will build temples and

shrines, and will bring gifts to the shrines. They will always take

care of the art of war and weapons, and they will diligently train their

bodies in weapons. Thus Quirinus will save the Roman

people."]

*Quirītēs: a term used to

refer to the Roman people

**Quirīnus: the name given

to Romulus after he was deified